Conrad Salinger

CONRAD SALINGER -

M-G-M ARRaNGER SUPREME

by RICHARD HINDLEY

"What a glorious feeling, I’m happy again"

Think of a production number from one of the great MGM musicals. Whether it be Gene Kelly splashing along the sidewalk from ‘Singin’ in the Rain’, Fred Astaire and Cyd Charisse ‘Dancing in the Dark’ from ‘The Bandwagon’, or Fred with Judy Garland as a ‘Couple of Swells’ in ‘Easter Parade’, the chances are you’ll be associating these famous performers with those equally well known arrangements by Conrad Salinger. What’s interesting is that even if he hadn’t been associated with the number of your choice, it was Salinger who eventually set the defining style of the studio’s musicals, something that took place soon after the start of his 23 year career there.

His life-long friend and associate, John Green, who was Head of the MGM Music Department in the 1950s, described him as the studio’s ‘star orchestrator, one of the two or three outstanding arranger/orchestrators in the entire field of musical theatre’. In a recent interview John Wilson described Salinger’s talents: "he could translate colour and mood into sound to produce the most startling production numbers. When needed he could write on a grand scale, as in the climax of ‘This Heart of Mine’ (‘Ziegfeld Follies’, 1946), and then he would paint delicate smaller scale sound pictures as in parts of ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ (1952)".

Jeff Sultanof, conductor, arranger and editor, describes it in technical terms: "Salinger’s genius was to fill the sound canvas with rich, beautiful harmonies balanced with contrapuntal lines, and then set them in basic orchestral colour groups, the combination almost too busy in some cases, but not quite. There are those who believe that MGM’s musicals are over-orchestrated and overdone musically, but I’ve rarely heard a musician complain about Salinger’s work, because it is skilfully written and yet inspired. And there is always room for the singer. This is why Salinger’s work continues to inspire orchestrators, even though few of us will ever have the opportunity to create that level of work since there are few movie musicals made today".

Salinger’s credentials are a case in point when it comes to music making in Hollywood, where three composers - Max Steiner, Alfred Newman and Erich Korngold - had established during the nineteen thirties a scoring style based on nineteenth century romanticism. Moving on to the Hollywood musicals from the 1940s, Salinger’s talents brought in a French sensibility to the musical scene, influenced by Debussy and Ravel, and, by implication, their acknowledged master, Rimsky-Korsakov, whose rich orchestrations left an indelible mark on both of them. Christopher Hampton, the late musician and writer, also credits Frederic Delius as an influence too, reminding us that he’d lived for most of his life in France, and whose music was deeply influenced by Impressionist painting. Hints of the legacy of these composers run through Salinger’s work and you can sometimes spot a dash of Respighi and Stravinsky as well. To understand why, you only have to look at his background.

"It’s a lovely day that’s all around you, count your treasures you are well-to-do…"

In its promotional publicity, Brookline, Massachusetts, describes itself as ‘a desirable commuter suburb of Boston’. John F Kennedy was born there in 1917, and its later musical residents included Arthur Fiedler, Serge Koussevitsky (a music professor from Moscow who became conductor of the Boston Symphony) and Roland Hayes (a renowned black American lyric tenor). Ironically, there is no mention of Conrad Salinger, born there on 30th August 1901. The music flowing from his pen would be heard by more people around the world than all three of these together. This image of Brookline gives an implication that he came from a wealthy and probably cultivated family, one that could afford to encourage his talents even after his graduation from Harvard in 1923. To complete his musical studies, he crossed the Atlantic to France where he was enrolled in the Paris Conservatoire. Yet this shift to another culture was enticing in more ways than one: Salinger was homosexual, and, by moving to Paris, he could turn his back on the puritanical and censorious society of his upbringing. (In fact Boston retained this reputation well into the 20th century, prompting the expression "Banned in Boston" - an unintentional pun mercilessly exploited in the sixties in the eponymous David Rose bump and grind composition - for MGM Records, to boot).

Salinger studied harmony and orchestration with André Gédalge, himself author of a famous work on counterpoint, and possibly Maurice Ravel as well. The tuition with Ravel is in dispute, but Ravel was certainly involved at the Conservatoire during this period, another of his pupils being Ralph Vaughan Williams. In any case, Ravel himself had studied under Gédalge - whose other pupils included Darius Milhaud and Arthur Honegger. But there would have been other influences at work on Salinger as well, for let’s not forget what a vibrant and exciting place Paris was at this time. Even after the ravages of the First World War it still remained the arts capital of the world, with jazz adding to the vigour of the music scene, aided and abetted by such luminaries as Josephine Baker who created a sensation with her performances of exotic primitivism.

Salinger spent a total of seven years in Paris, and apart from learning to speak fluent French, he would have been exposed to the popular French music of the day. Running throughout his work are cheerful jaunty motifs, redolent of the boulevards of Paris: think ‘Mimi’ by Rodgers and Hart and ‘Ah Paree!’ from Stephen Sondheim’s ‘Follies’, to name other writers who have consciously parodied that French boulevard style in their songs. This influence, with its lightness of touch mixed with the solid academic background from the Conservatoire (he was a proficient composer and conductor, too) was to serve Salinger brilliantly during his career, although the technicolor world of the French capital as portrayed in ‘An American in Paris’, ‘Funny Face’ and ‘Gigi’ lay quite a few years ahead. One wonders what the look on the face of André Gédalge would have been, were he to have heard ‘Sinbad the Sailor’, Salinger’s reworking of Rimsky-Korsakov’s ‘Scheherezade’ some 25 years later for Gene Kelly’s ‘Invitation to the Dance’.

"Your troubles there, they’re out of style, for Broadway always wears a smile…"

Returning to the art deco splendour of New York in 1929, Salinger was very much a cultivated ‘man of the world’, always impeccably dressed, an image of sartorial splendour that he’d retain throughout his life, quite the opposite of the public’s idea of how many musicians present themselves. Indeed, closer inspection of a 1937 photograph taken of him joking with co-worker John Green reveals a framed reproduction of the Dutch master Vermeer: an unexpected adornment for the wall of his office, where presumably the photograph was taken, but certainly in keeping with his refinement.

His professional career started at Harms, the music publishing company, as a staff arranger. He then moved into the world of Broadway shows and the movie industry, for at this time some of it was still based in New York. His first film experience was for Paramount, both at their Astoria Studios on Long Island and the Paramount Theatre on 41st Street NYC. This was the era when first run movie releases were preceded by spectacular stage shows. The head of the department who engaged him was Adolph Deutsch, who would reappear in Salinger’s career at MGM. Salinger is acknowledged to be an uncredited arranger, along with John Green, for the Lubitch musical ‘The Smiling Lieutenant’ (1931).

Between 1932 to 1937 Salinger concentrated on arranging for a dozen Broadway shows, initially assisting Robert Russell Bennett, who considered him to be a protégé. David Raksin and John Green were other noteworthy arrangers on some of these shows, again names that would reappear at MGM. Green in fact scored the Broadway show ‘Here Goes the Bride’ in 1931 on which Salinger worked. Other titles from this period include ‘George White’s Scandals’ (1936) and ‘Billy Rose’s Jumbo’ (1935) with a Rodgers and Hart score. This one would eventually be filmed at MGM in the sixties after delays of many years caused by contractual restraints. Of particular interest is ‘Ziegfeld Follies of 1936’ which boasted a sophisticated score by Vernon Duke and Ira Gershwin and a cast including Bob Hope, Fanny Brice and Eve Arden. This is one of the few instances where we can now hear a new cast recording utilising the original arrangements, all painstakingly reconstructed. Issued recently on CD by Decca USA, it evocatively conveys the original intentions of the production, although the many glorious arrangements, the work of three other arrangers in addition to Salinger, regrettably remain unsigned.

"I’m on my way, here’s my beret, I’m going Hollywood…"

Salinger’s transition to Hollywood was not instantaneous: his first assignment was for Alfred Newman at Goldwyn-United Artists in 1937, but the experience proved unenjoyable and he returned to New York and Broadway. He was also assigned to the the Astaire/Rogers musical ‘Carefree’ (1938) at RKO, where his work as arranger/orchestrator went uncredited, as was that of his co-worker Robert Russell Bennett. But by now Salinger’s fame and reputation had spread throughout the industry, and he’d already met up with Roger Edens, an accomplished musician and writer, a man of many talents who acted virtually as an associate producer at MGM. Edens was a close colleague of songwriter producer Arthur Freed, who was to create the studio’s most prestigious musicals. This he achieved by surrounding himself with a handpicked team composed of the studio’s top talent, the legendary ‘Freed Unit’. Freed’s clout and standing ensured its members were virtually on call for his productions, much to the occasional annoyance of other producers at the studio.

Edens arranged that Salinger should immediately join the Unit and he was eventually offered an irresistible long-term contract that drew him permanently to Hollywood. This was a well worn path for countless actors, directors and musicians since the start of talking pictures, for Hollywood had always had the drawcard of fame with its concomitant wealth to seduce talent to its doors. So Salinger gave his regards to Broadway and started a career at MGM. His contribution to some 50 musicals would be inextricably linked to the fortunes of the MGM dream factory.

"Where troubles melt like lemon drops away across the chimney tops, that’s where you’ll find me…"

His first assignment was on ‘The Wizard of Oz’(1939) as the uncredited orchestrator of the ill fated ‘Jitterbug’ number, unfortunately destined for the cutting room floor, although the music track remains in existence. ‘Strike Up the Band’ (1940) brought him his first on-screen credit and from then on the credits run thick and fast, his work on all the musicals directed by Vincente Minnelli from 1942 being particularly inspired. Minnelli was also an import from Broadway as well as being a self-confessed Francophile. Their collaboration worked to such an extent that, as John Wilson aptly puts it, ‘he heard what Minnelli saw’. No wonder his work reached new highs. Jeff Sultanof describes it as being ‘beautiful to hear and sophisticated in content. I believe the other orchestrators at MGM were influenced by Salinger. Wally Heglin’s arrangements before and after 1943 show the Salinger influence as an example’.

During these years Salinger and Roger Edens created a powerful synergy in their contribution to the production numbers: Edens would sketch out the mood, tempo, texture and setting of a prospective number, after which Salinger fleshed out the details. ‘The Trolley Song’ in Minnelli’s second movie musical ‘Meet Me in St Louis’ (1944) is the perfect example, and a description of Judy Garland’s recording of it is vividly described in a book by Hugh Fordin on the Freed Unit: ‘even after the orchestra’s first reading of his arrangement…an excitement spread among those playing and listening. Then, when Judy came in with her dead-sure instinct of what she was to deliver, the ceiling seemed to fly off the stage…..Salinger’s arrangement was a masterpiece. It conveyed all the colour, the motion, the excitement that was eventually going to be seen on the screen. With the remaining numbers and the background scoring for this film as well as all the work he was to do thereafter, Salinger always maintained sonority and texture in his writing, which made his a very special sound and style that has never been equalled in the American movie musical’.

For the next Minnelli collaboration, ‘Ziegfeld Follies’ (1946) we get sumptuous and exotic textures, notably in the lavish production numbers ‘Limehouse Blues’ and ‘This Heart of Mine’. In the latter Salinger includes French horn obbligato passages worthy of Richard Strauss to transport us well and truly ‘over the top’. But most importantly, in both these numbers, it’s the narrative - the dramatic story telling which bursts through the confines of those popular songs - that pushes the art of the arranger well into the realms of composer.

Jeff Sultanof points out that the Salinger style ‘was also tailored for the microphone, an important distinction’, and this is the key explanation of that unique MGM sound. In the late twenties, Bing Crosby had studied the limitations of 78 rpm recording techniques, tailoring his voice accordingly. In similar fashion, Salinger accepted that the optical sound recording of the day, the process that preceded tape recording by photographing the audio onto film - had a limited dynamic range, with a consequent loss in quality between live performance and final release print. Despite those huge Hollywood budgets and virtually limitless musical resources at the studio, he realised his writing sounded best with around 38 players, more in keeping with the pit orchestras of Broadway. Any choral backing was consequently scaled down to match, thus creating something relatively easier (and less costly) to record. But this also had the advantage of creating an orchestra from the cream of talent available. As described by John Wilson: ‘it was really a dance band line-up with a string section. Many of the musicians had been star players with such as Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey. Si Zentner, for example, usually led the trombones. And they were augmented as required from film to film. Above all, though, the orchestra was noted for its warmth of the brass sound and the ‘fat’, almost old-fashioned string sound. You have to bear in mind that America received a flood of refugees from Europe, particularly from Russia, and that many brought with them the Jewish traditions of string playing. So the sound is rich and vibrant, full-bodied, at times almost flashy, with a strong vibrato, and relentlessly brilliant.’

"Forget your troubles come on get happy, you’d better chase all your cares away…"

Throughout his career at MGM, Salinger also distinguished himself as a composer of background scores for many of the musicals in addition to arranging the numbers, such as ‘Till the Clouds Roll By’ (1946) ‘On the Town’ (1949) and ‘Show Boat’ (1951) for which he shared an Oscar Nomination with Adolph Deutsch for ‘Best Scoring of a Musical Picture’. For some dramatic productions, such as ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’ (1954) and ‘Gaby’ (1956) he scored the entire film, utilising as thematic inspiration Jerome Kern’s song for the former, and Richard Rodgers’ ‘Where or When’ for the latter. With the introduction of tape recording, and later on stereophonic recording, he saw the studio revert to the larger orchestra, which suited the new wide screen image and spectacular adaptations of Broadway musicals like ‘Brigadoon’ (1954) and ‘Kismet’ (1955) and ‘Silk Stockings’(1957).

These gradually took over from the staple musical output that had been the hallmark of MGM into the early fifties, so that the release of such masterpieces as ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ (1952) and ‘The Bandwagon’ (1953) signalled the gradual demise of original scripts and the scaling down of musical output in general. Christopher Hampton considers this period to be the epitome of Salinger’s endeavours, when he created ‘the de luxe quality of orchestral writing exemplified by ‘Dancing in the Dark’, ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ and ‘The Heather on the Hill’ (from Brigadoon) - a quality born of his feeling for beauty of timbre, for mood, for atmosphere, for nuance, above all for line, the give-and-take of melody and countermelody’.

By the mid fifties, Metro was starting to fall apart, with producers no longer under contract and the famous roster of stars well on the wane. Consequently we find Salinger looking in other directions for employment. His credit, as composer, is to be found in the TV series ‘General Electric Theatre’ (1954), ‘Wagon Train’ (1957) - quite a contrast to frothy musicals, but in the distinguished company of such other composers as David Raksin, David Buttolph and Gerry Goldsmith - and ‘Batchelor Father’ (1960 series). Even so, Salinger still worked as orchestrator on the dwindling number of musicals, two of them with Paris settings. ‘Funny Face’ was directed by Stanley Donen in 1957 and has the notable ‘Bonjour Paris’ number, for which Salinger provides a brilliant kaleidoscopic arrangement that describes the bustle and panoramas of the city in its underscoring of Roger Eden’s song. ‘Gigi’ (1958), proved to be the last production for the Freed Unit that was not developed from a Broadway show and Salinger’s last collaboration with Freed and Minnelli.

One surprise is to discover that he was the uncredited orchestrator on the blockbuster western ‘The Big Country’ (United Artists, 1958). The score, composed by Jerome Moross, is regarded as one of Hollywood’s best. One wonders what exactly Salinger’s contribution was, given his stature and years of experience against those of Moross, a relative newcomer to the Hollywood big league. There has to be an irony about those opening bars - the composer describes the spinning wagon wheels of the main title, but his orchestrator is the man who had created and arranged the ‘Trolley Song’ wheel motif! Nevertheless, a compensating recognition was about to come to Salinger, one that would bring his name to prominence for the record-buying public.

By the late fifties Verve Records was identified with recordings featuring top jazz instrumentalists and singers. All the more unusual then, that Salinger was approached to prepare an instrumental album of his arrangements. This was the idea of Buddy Bregman, the label’s star arranger/conductor and head of A & R, a man with a huge list of impressive credits. By then he had already accompanied Ella Fitzgerald on both her Cole Porter and Rodgers and Hart Songbook albums, two of the top twenty-five albums in almost every magazine poll and Record Guide Book. These, plus the Bing Crosby album ‘Bing Sings Whilst Bregman Swings’ had all gone platinum. Bregman had also recorded several successful big band albums of his own. Norman Granz, chief producer at Verve (and creator of the label itself), gave Bregman the go-ahead, and the album started to take shape. Bregman recalls the 12 tracks, all of his own choosing, were mainly based on Salinger’s vocal arrangements from the MGM musicals, scored for the classic line up of 40 musicians that he’d hit upon for the MGM Studio Orchestra - although the sleeve notes of the album refer to the tracks as ‘(the) personal favourites of Mr Salinger’. It was recorded at Capitol Records on Vine Street, Hollywood, in Studio A, and, as Bregman recalls: ‘Connie Salinger attended….he left everything to me….he loved everything and the musicians he did know he interacted with. He was thrilled that I thought of this idea’. Bregman describes him as ‘a sweet man, a shy guy who always smiled’, in fact the antithesis of Bregman himself who, for this album, had the magnanimity to step aside from his usual credit in deference to this other great musician.

The stereo album, ‘A Lazy Afternoon’ (Verve LP MGV 2068) was issued as ‘The Conrad Salinger Orchestra Conducted by Buddy Bregman’- and you don’t find many accolades like that in the recording industry. Bregman remains proud of the achievement: ‘It’s a great album - not for my work - but for the idea that I put the whole thing together and his great charts!’ If you were to find a copy of this rare album, you may agree that it’s one of the greatest, and a special one at that, for there must be no other where it’s the arranger who has top billing. But Salinger himself was not a recording artist and was unknown to the general public. Perhaps this was a disadvantage when it came to sales of the album, for in USA they proved to be disappointing. Certainly Verve Records’ clichéd dreamy girl cover – de rigeur for orchestral albums of the day – gives no hint of its unique contents. Consequently its British release was scaled down to an extended play 45rpm issue (HMV 7EG 8322), although it fared slightly better in Australia, where it appeared on Astor, a budget label of rather poor audio quality. Interestingly, Bregman admits the Salinger influence for his subsequent instrumental album of Gershwin songs featured in the movie ‘Funny Face’ (Verve LP MGV 2064). What wonderful CD reissues these two albums would now make!

‘Billy Rose’s Jumbo’ (1962, aka ‘Jumbo’), the last MGM musical on which Salinger worked, reunited him with the Rodgers and Hart score from his Broadway past. It turned out to be not only the last musical for the studio that has the identifiable ‘MGM sound’ but for Salinger it was both a completion and a full stop, for by now the entire future of the studio looked bleak. Hollywood continued to respond to the demands of a younger audience - with the realisation that the rock era was truly here to stay - plus even further declines in box office receipts. Eventually the studio would be scaled down solely for television production and by 1969 a new regime would appear, headed by James Aubrey, who would order the destruction of the entire music library - an act, viewed in hindsight, that symbolised the imperatives of accountancy over any cultural legacy that might have been preserved.

"then goodbye, brings a tear to the eye…"

Conrad Salinger lived in Pacific Palisades, one of the wealthiest and most beautiful suburbs of Los Angeles. It was here that, on 9th July 1961, he took his life. He was 59 years old. The international movie database notes the cause of death as a ‘heart attack while sleeping’, surely a more graceful and dignified public record of his passing.

Perhaps this is where we should take a few bars rest, those of us who remain ‘waltzing in the wonder of why we’re here’ to contemplate the achievements of this talented man. Hollywood, with its mega Dream Factory, may well have delivered him fame and riches, but perhaps at the expense of peace of mind. We have seen how his life’s work became linked to an enormous studio, whose fortunes and production of its once staple musical output both declined. During this period Salinger worked with its top talent, nourished by scores from the nation’s greatest songwriters: Kern, Berlin, Gershwin, Porter, Arlen, Youmans, Lerner and Loewe, Burton Lane, Hugh Martin, Arthur Schwartz, Harry Warren, Comden and Green, and not forgetting Arthur Freed himself, as lyricist. He became, as Jeff Sultanof puts it ‘perhaps the single greatest orchestrator for motion pictures that I’m aware of…. I believe the following orchestrations changed the course of popular orchestral writing: ‘Dancing in the Dark’, ‘Mack the Black’ (from ‘The Pirate’, 1948), ‘Singin’ in the Rain’, ‘This Heart of Mine’ and ‘The Trolley Song’.

"now the young world has grown old, gone are the silver and gold…"

The Metro musicals, like all movies, were once a disposable commodity, to be released one week and forgotten the next. But with the advent of sales to television and later the release of the ‘That’s Entertainment’ compilations from the MGM vaults, a new generation came to appreciate their merits. From the 80s they’ve been re-released on videotape, laserdisc and now DVD as well as on CD by the Rhino label. These CDs have restored the songs and numbers to the same duration as performed in the films, unrestricted by the timing constraints of previous 78rpm and LP releases.

Although Salinger was part of a vast team of talent, his contribution has nevertheless continued to be appreciated. In 1985 Barbra Streisand insisted on his orchestration of Jerome Kern’s ballad ‘Bill’ from ‘Show Boat’(1951) for her Broadway Album, which was then adapted by Peter Matz. Although a new arrangement had been presented to her, she could not forget seeing the movie as a child, with the Salinger arrangement staying in her memory, and that was the backing she wanted. The next significant recognition was on a much bigger scale: the release in 1990 of the Chandos CD ‘A Musical Spectacular: Songs and Production Numbers from the MGM Musicals’, recorded in London by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Elmer Bernstein. The arrangements were lovingly restored by the instigator of the project, Christopher Palmer, whose detailed sleeve notes celebrated Salinger’s work for the first time since Buddy Bregman’s album. Palmer described him as ‘the real hero of the album’ which, thirteen years later, is in its third release, the latest version at last giving Salinger’s credit prominently on the front cover.

"But came the dawn, the show goes on, and I don’t wanna say godnight!"

March 2003 signalled an even more exciting event, when John Wilson presented his ‘That’s Entertainment’ concert at the Royal Festival Hall, London. John had set himself an enormous task of restoration to scorepaper of many of his favourite MGM numbers by accessing remnants of the originals, for the most part retained in sketch form for reasons of copyright, but ‘long hidden in deepest storage’. He assembled an 85 piece orchestra with an enormous choir of 100 to perform creations of many talented arrangers: Skip Martin, John Green, Andre Previn and Robert van Epps - but the most prominent name was that of Salinger. Unlike the Chandos recording, John ensured his line-up included many fine musicians familiar with the jazz idiom to recreate a much more authentic MGM sound. The audience, to quote John, ‘went bananas’ - proof indeed that these scores should have a secure life in the concert hall, in happy coexistence with the originals on the soundtracks of the movies themselves.

Salinger may well have had to deal with problems both professional and private at the end of his life, but we can still enjoy the legacy of his talent - a talent that enhances and sometimes transcends those glorious Metro musicals of his day.

Author’s postscript

In researching this article I acknowledge information from the following:

The book ‘MGM’s Greatest Musicals: The Arthur Freed Unit’ by Hugh Fordin, published by Da Capo Press New York 1996 (the book was originally published in 1975 under the title ‘The World of Entertainment! Hollywood’s Greatest Musicals’); Christopher Palmer’s sleeve notes for the RPO Chandos CD; John Wilson talking to Malcolm Laycock for BBC Radio 2; John Wilson’s programme notes for his ‘That’s Entertainment’ concert, supplied by RFS member Ken Bruce; and Gary Zantos, who has an encyclopaedic knowledge of the MGM studios.

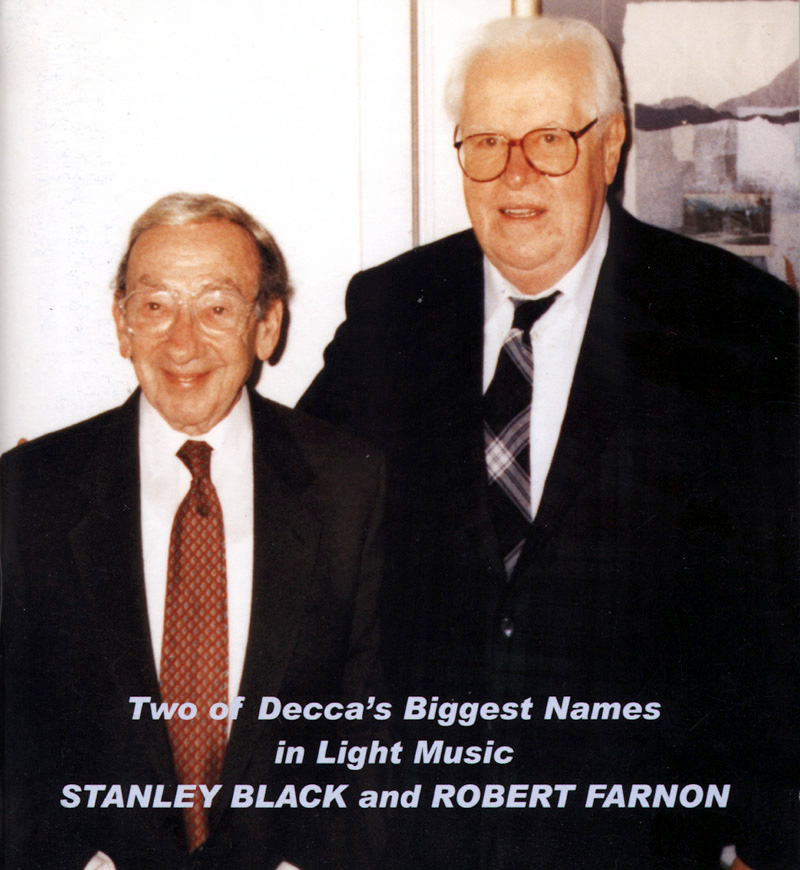

Thanks are also due to Buddy Bregman, and especially to Jeff Sultanoff - his enthusiasm and supplying of invaluable information was a great inspiration. In addition to his conducting, arranging and editing activities, Jeff is also an author and Assistant Professor of Music at Five Towns University, Long Island, NY. (He modestly revealed that he has edited and recopied fifty-two Robert Farnon compositions and arrangements, which Bob has seen and approved. Working in conjunction with John Wilson, he is preparing a Robert Farnon edition of definitive versions of his music). Thanks also to my friend William Motzing, Lecturer in Jazz Studies, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, for checking through the final draft. (Bill has recorded the Main Title from Robert Farnon’s ‘Bear Island’ score on his 1994 double CD ‘Best of Adventure’ with the City of Prague Philharmonic).

Richard Hindley (June 2003)

This article first appeared in the Robert Farnon Society’s magazine ‘Journal Into Melody’ in September 2003. The author Richard Hindley is a respected Film Editor working in Australia. Richard has been a member of the Robert Farnon Society since its very first meeting in 1956.

A large number of Conrad Salinger’s scores for MGM have been reconstructed by the British conductor John Wilson, and they were featured in a widely acclaimed Promenade Concert in London on 1 August 2009.

Most of the tracks from the Conrad Salinger/Buddy Bregman LP mentioned in this article are now available on various CDs in the Guild "Golden Age of Light Music" series. For more information go to www.guildmusic.com