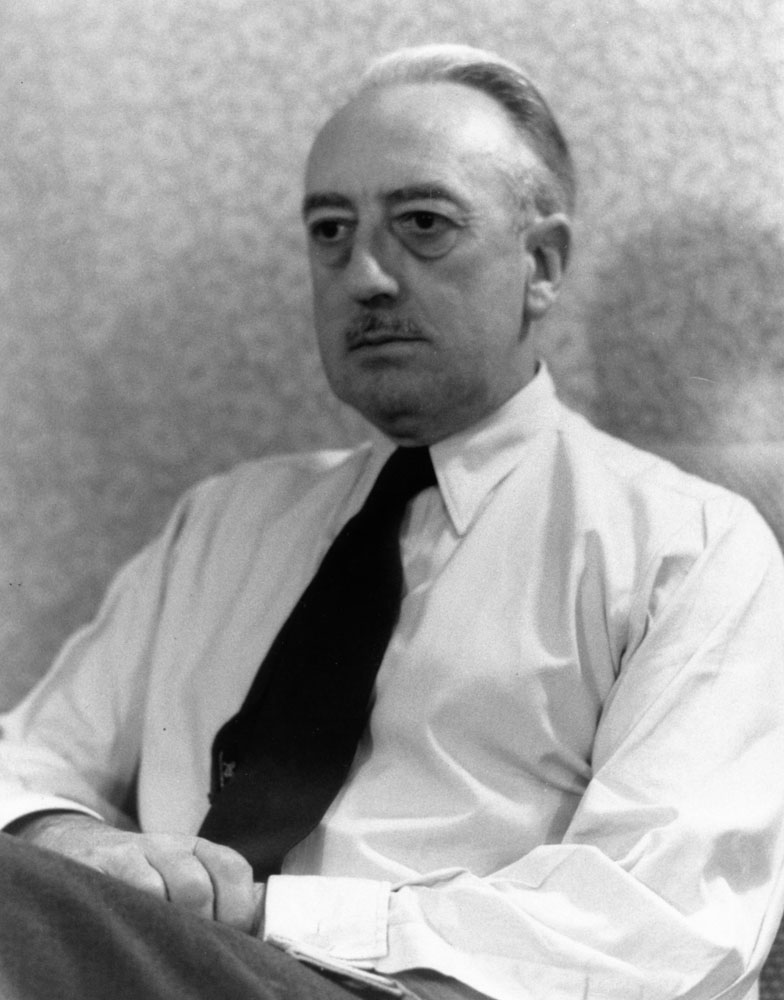

Cecil Milner

If any readers had doubts about the important work carried out by the ‘backroom boys’ of the music industry, this fascinating life story will certainly be an eye-opener! Rarely seeking the limelight themselves, they often created the sounds we all grew to love so much.

OUT OF THE SHADOWS: THE CECIL MILNER STORY (1905-1989)

by Colin Mackenzie and Timothy Milner

Cecil Milner has sometimes been described as one of light music’s respected "backroom boys", a statement which, we would argue, does not do full justice to his prolific career in music. In his prime Milner was a craftsman, his arranging and composing skills being among the best in the business. Although film music was his forte, he was also part of the light music scene for many years, including a lengthy and successful association with Mantovani which began in 1952.

We cannot estimate how much music Cecil was responsible for, the list seems endless. There are several hundred compositions, arrangements and incidental pieces of music, but to arrive at an accurate total is impossible. The reason for this is simply explained and it concerns his arrangements of other composers’ work. Music publishers paid Cecil a standard fee for each arrangement he made, and that was the end of it. He could only claim royalties for arrangements when scoring a non-copyright piece of music, and it is these that show up in his royalty statements. The others do not. We must thus turn to the correspondence in Cecil’s archives to locate some - but not all - of the details of his many arranging commitments.

At least we are able to pigeonhole his contribution to music into six main categories:

firstly, there were his early classical compositions; then a large amount of incidental music composed for films, interspersed with arrangements of other writers’ work. His own light music compositions were used for all sorts of purposes and there were also various pieces of cueing music devised for mood music libraries.

Finally, there were his arrangements for Mantovani. Of these we estimate a total of over 250 during a period of 22 years. It is these, in particular, that remind us that Mantovani, a perfectionist who demanded the very best from those who worked for him, would not have employed Cecil as one of his main arrangers had there been anything remotely second-rate about him.

Even so, some of the light music cognoscenti view Cecil as just another arranger among many and not a very prolific one at that. Others profess ignorance of his career. One much respected British light music composer, a contemporary of Milner’s, when asked at a meeting of the Robert Farnon Society if he knew Cecil Milner, replied that he had never heard of him.

Admittedly, the very nature of the man has contributed to his lack of modern day recognition. Like many of his associates, Cecil did not seek the limelight and never courted publicity. It was just not part of his nature; he really wanted none of that. He relied on his compositions and arrangements to enhance his reputation, leaving a variety of music publishers to distribute his own work around the world.

In further considering why his worth has not been fully recognised, it is only in recent times that the arranger has been acknowledged as a craftsman in his own right. During Cecil’s main period of activity, which embraces much of his time with Mantovani, it was unusual for light orchestras to include the accredited name of an arranger on the record label or the album sleeve. Thus his name was rarely before the general public or even light music buffs.

We should understand, too, that Cecil wrote a relatively small number of full-length (i.e. over three minute) melodies. He was just too busy arranging other work. Except for his earliest classical compositions which are bound in hardback, he did not keep any copies of his own work, preventing us from assessing its full volume. Additionally, his work was automatically retained by film companies and mood music libraries as their property. Franck Leprince, a respected musician and arranger, informs us that "until the 1970s it was unusual for the composer of a film score to be allowed to keep any of his sheet music after recording the score." Even so, you might assume that there would be a stockpile of Cecil’s film arrangements awaiting discovery somewhere or other until Franck explains that "the great studios in the USA and in England all burned pile after pile of original scores and sheet music, simply because they were always running out of space."

Applying this criterion to the smaller film studios, Timothy Milner is convinced that many of his uncle’s film and incidental music arrangements were disposed of or thrown away. Ominously, a comment in a recent letter he received from a leading music publisher tends to confirm this view: "The sheet music for pretty well all our old production music titles has disappeared long since, if it even survived beyond the recording session. Nobody in those days expected that background music would be of any interest to future generations."

Nevertheless, there are existing sheets for original Milner works held in the British Library includingAerial Activity, Cloud Drifts, Pursuit, Shipwreck, Mailed Fist, Fly Past, Downland, Russian Marching Song, Saluting Base and State Drive. Of the many others, however, there is little or no trace anywhere. As you might guess, Timothy (who can be contacted on 01304-852493) wishes to hear from any reader who can throw light on the whereabouts of his uncle’s missing compositions, arrangements and film music.Fortunately, there are enough surviving letters from musicians and music publishers in Cecil’s archives to provide us with a rare insight into the professional activities of a "musical composer & arranger" (as Cecil’s invoices were headed). In relating his life story, we intend to prevent him being typecast in the future as a mere run-of-the-mill arranger who really didn’t achieve very much.

Cecil’s story begins on 20 April 1905 in Merton, Wimbledon, as the first born son of Ernest Edward Milner. Originally from Chesterfield, Ernest was involved with the Elder Dempster shipping business in Liverpool before coming to London in 1903 to help shape the future of Elders and Fyffes. Known as "The Great White Fleet", the company’s ships, numbering over 100, transported passengers to the West Indies and, as the name Fyffes implies, imported bananas and fruit from the Caribbean and Cameroon. After spending 55 years in the company’s service as a much respected director, secretary, treasurer and chief accountant, Cecil’s father retired on the last day of 1953.

In whatever spare time he had in the 1920s, Ernest founded the Wimbledon Lyric Players, an amateur operatic group which still exists to this day. Married to Marie Elizabeth Martindale, they had two sons: Geoffrey Ernest, who followed his father into the shipping business - between them they accumulated some 90 years of service - and Edward Cecil, whose precocious talent made it inevitable that he would follow a career in music. As a youngster, Cecil took part in his father’s amateur dramatics - a family photograph shows him dressed up as Charlie Chaplin - and he would even play piano with his brother on clarinet when the Lyric Players put on a production. Geoffrey married Dorothy McBean, formerly a glamorous actress and dancer on the West End stage. At one period she understudied her close friend Jessie Matthews. Cecil, on the other hand, married Phyllis Platel, a fellow student at the Royal Academy of Music, just before the outbreak of war at St Paul’s RC Church, Dover on 12 August 1939. During WW2 Geoffrey, who held an extra master’s certificate, became Lieutenant Commander G. E. Milner, MBE, RD in the Royal Naval Reserve. He was mentioned in dispatches and awarded an MBE for courage, resolution and endurance when his cruiser was torpedoed by a German U boat in the South Atlantic in 1942 with the loss of over 450 men. During his distinguished merchant naval career he became a member of the Institute of Naval Architects.

The Milner family home was Orkney at 40 Merton Hall Road, Wimbledon. From an early age both brothers were keenly interested in music, Cecil playing classical piano at London music festivals at the age of nine, his brother at 10. In those early days Cecil was a guest at a meal given to honour Puccini at one of the London hotels. The brothers attended King’s College in Wimbledon, where Cecil obtained credits in History, Latin, English, French, German and Mathematics. He later attained a certain fluency in Spanish and Russian.

During the General Strike of April 1926 Cecil volunteered to be a temporary special constable in the Wimbledon area. At this age (21) he was already well known in London music circles, for a letter from the Wimbledon Conservatoire of Music, dated 4 February 1927, invited him to the formation of a local flute club.

Funded by his father at 14 guineas a term, Cecil attended the Royal Academy of Music in Marylebone Road from 1924 until 1932. Tutored on piano by Ambrose Coviello, then Claude Gascoigne, he studied composition and harmony under Norman O’Neill, the noted composer. A postcard written by O’Neill in 1927 drew Cecil’s attention to a comment or review - it is not clear which - by Harold Thompson, given to O’Neill by Basil Cameron, the famous conductor. In describing Thompson as "one of the best critics we have", O’Neill cautioned Cecil not to "let that swell your head!" A friend of Elgar and Delius, O’Neill’s early death in March 1934 at the age of 58 resulted from complications arising after a collision with a milk cart in central London. He had been a strong source of inspiration and encouragement to Cecil, as well as being a close friend, and his passing came as a great shock. Following the ordinary curriculum at the Royal Academy, Cecil had two weekly lessons of one hour each on piano and one on composition. Harmony and counterpoint were also given as a one hour weekly lesson, although, unusually, Cecil’s administrative record gives no indication that he received harmony until 1928. Cecil, who possessed absolute perfect pitch, was instructed in aural training, too, as well as sight reading, score reading and transposition.

As well as collecting half a dozen bronze and silver medals, he earned the highest awards, the Academy’s certificates of merit for aural training (1928), pianoforte (1929) and conducting (1932), the latter shared with Cedric King Palmer. He also shared the Oliveria Prescott Prize of full scores with Beryl Price in 1932 as a distinguished student of composition. Marking his success, his proud father presented him with a splendid Bechstein Boudoir grand piano, which is still in the possession of the Milner family today.

One of Cecil’s first compositions, In a Pine Forest, a nocturne for orchestra, was performed at the Festival of British Music at the Royal Hall, Harrogate on 26 July 1929, under the baton of Basil Cameron, the renowned conductor associated for many years with the Sir Henry Wood promenade concerts. Unfortunately, the concert programme, prepared in advance, credited the piece to "Eric" Milner. Cecil had better luck, however, when a photograph of himself with Percy Grainger was captioned in the Yorkshire Evening News of 25 July, for he found himself described as a "famous composer"!

As well as the Australian born Grainger (1882-1961), Cecil was on friendly terms with other luminaries of light music including his life-long friend Clive Richardson (1909-98), also Roger Quilter (1887-1953), Richard Addinsell (1904-77), Vivian Ellis (1903-96) and Cedric King Palmer (1913-99), all of whom possessed a sound knowledge of classical music.

King Palmer, in particular, contributed some 600 works to the recorded libraries of several London music publishers, a path Cecil was to follow, and conducted popular arrangements of the classics on BBC radio during the 1940s and 1950s. In later years, both he and Clive Richardson used to gather with Cecil for their annual summer reunion at the Milner holiday home in St Margaret’s Bay.

Basil Cameron also conducted Cecil’s Pastoral Suite for Orchestra at Hastings on 28 February 1930, and performed another of his works, Spanish Rhapsody. Meanwhile, one of the country’s leading conductors, Dan Godfrey, directed the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra in performances of thePastoral Suite in the concert hall of the Bournemouth Pavilion. In Stephen’s Lloyd’s biography of Godfrey (later Sir Dan), he is profiled as the founder and conductor of the first British "permanent fully-salaried municipal orchestra", a man who was prepared to give up and coming talent a chance to have their compositions aired. Apparently, Godfrey approved of Cecil’s Pastoral Suite for he made a transcription of it for military band.

For young Milner there were even more ambitious projects ahead. After translating G. Martinez Sierra’s Margarita en Ia Rueca from Spanish, he adapted the work into libretto for a two act operaEngracia, composed between 1930 and 1932. This was probably the work that won him the Oliveria Prescott prize for a composition of outstanding merit. After Milner himself had conducted the aria from the opera at the prestigious Queen’s Hall in March 1932, Engracia was staged the following December in the Royal Academy of Music’s theatre under the baton of B. Walton O’Donnell. The well-known singer Janet Hamilton-Smith (later Bailey), who starred in the West End musical Song Of Norway in the 1940s, sang the aria on one of these occasions. At one period Norman O’Neill planned to have the opera staged in one of Germany’s leading opera houses, but the contract could not be honoured because of a fire.

Cecil’s other compositions of this period included a Quartet for Strings in D minor, a Fugue in A minor, three songs for sopranos, and a String Quartet no 1 in G (Variations for Orchestra) performed in the Duke’s Hall of the Royal Academy. In September 1930 he was offered a sub-professorship at the Royal Academy, but turned it down perhaps because he was too busy or because he did not wish to seek publicity. He was always quiet and retiring and eschewed the limelight.

It comes as a surprise then to learn that while making his name as a classical musician Cecil was a member of the five piece Eclipse Dance Orchestra for some five years. A band photograph identifies him playing on trombone, but this accomplished musician was equally proficient on saxophone (alto, soprano and tenor), clarinet, violin and viola, timpani and, of course, piano. He supplied orchestrations for the band which, alas, was not recorded by any of the major labels.

One of the Academy’s most promising students was now at the crossroads: having become a Licentiate of the Royal Academy, should he now follow a career in classical music or look elsewhere for opportunities? On leaving his alma mater he caused some ripples by starting to arrange and compose music for stage, concert hall and film. This was undoubtedly where the money was to be made, and Cecil hastened to follow several of his contemporaries into the business of orchestrating black and white movies and newsreels produced by the Gaumont British Picture Corporation from studios at Lime Grove in Shepherd’s Bush.

Louis Levy, its managing director, valued Cecil’s contributions highly, as did its senior music editor, Bretton Byrd, a composer, conductor and pianist who had joined the company in 1930 after playing piano in silent movie cinemas. Byrd, who described himself as a specialist in film music direction, composition and conducting with expertise in the exact synchronisation of music with action, often worked with Cecil during the next twenty years. Milner was part of a team that included the likes of Hans May, Hubert Bath, Jack Beaver and Mischa Spoliansky, all ultimately well known in light music circles.

A trade publication, the British Film and Television Yearbook (1955-56) lists Cecil as the composer and orchestrator of about 50 movies, usually in collaboration with others. In fact, he was involved in many more films for Gaumont British and Gainsborough as well as others. Initially preparing music with Byrd for Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes, Milner found work, too, on Hey Hey USA, Bank Holiday, The Citadel and They Drive by Night (all from 1938), Inspector Hornleigh, So This Is London, Murder Will Out, Confidential Lady (all in 1940) and Dressed to Kill, The Good Old Days and Carnival.

A list in his handwriting also shows that he "dealt with" Gaumont British between 1939 and 1941 for films such as Neutral Port, For Freedom and I Thank You and assisted Byrd on the Warner movies George & Margaret, Two For Danger, That’s The Ticket, The Briggs Family, The Midas Touch and Hoots Mon. He was associated, too, with Denham Studios for Busman’s Honeymoon and the Gilbert and Sullivan company for A Window in London, both in 1940.

In his long career Cecil scored for British Lion, MGM, Twentieth Century, Errol Flynn Theatre movies and the Douglas Fairbanks Jr. series of TV films, more of which later. His incidental music was used in Gaumont newsreels, Pathé Pictorials, BBC and ITV newsreels, documentaries and advertising features. It should be understood that in the late 1940s and early 1950s some 12 million people visited cinemas annually around the British Isles so the market for films of all sorts was a strong one. In the early 1950s several of Cecil’s mood music library titles were extensively featured in American movie productions. The list of film shorts is a formidable one, perhaps numbering over 200 titles, with most of the music, probably drawn from existing compositions, appearing in such diverse productions as Rembrandt, Princess Margaret, Tanganyika Today, Bushtucker Man, Thirteenth Green, Farnborough, Capital City, Mau Mau and even Glen Orbits the Earth!

Some of the titles formed part of the popular Scotland Yard film and TV series during the 1950s. Among episodes for which Cecil received royalties were The Missing Man (1952), The Candlelight Murder (1953), Night Plane To Amsterdam, Fatal Journey, The Mysterious Bullet and The Blazing Caravan (1954), Murder Anonymous and The Silent Witness (1955), The Wall of Death, Destination Death and The Case of the River Morgue (1956), The Mail Van Murder, The White Cliffs Mystery andThe Case of the Smiling Widow (1957), Night Crossing (1958), The Ghost Train Murder and The Unseeing Eye (1959) and The Last Train (1960).

The theme music was Milner’s Mailed Fist, first assigned to Chappell on 31 May 1951. In production from 1952 to 1961, the series started out as a cinema second feature before transferring to television. Made at Merton Park Studios in South West London, the episodes concentrated on true-life cases drawn from the annals of Scotland Yard and were fronted by the well-known criminologist Edgar Lustgarten.

Milner’s work for Louis Levy at Gaumont British continued in difficult circumstances throughout the War. When his associate Charlie (Charles) Williams left the company in 1943, Cecil wrote to the corporation to ask for assurances that Williams’ departure would not affect his own work there. Levy’s reply was reassuring: "I have been very satisfied with your work for us of late, and, according to our plan, you should be very busy for us in the near future."

In collaboration with Bretton Byrd, who, as we have noted, had overall responsibility for the company’s film scores, Cecil was busy before and after the War. Interestingly, Byrd’s letter to Cecil in October 1947 outlines some of the difficulties associated with preparing film music. No doubt many other light music arrangers at that time felt as exasperated as Byrd did: "I have been definitely promised the next picture by Mr Corfield, and he has expressed great satisfaction over the last job, mainly because I was able to keep to his original budget in spite of retakes due to recording technical trouble". He concluded, "It’s terrible, he admits he knows nothing about music, and his one concern is that whatever goes into the picture as background music, should not interfere with the dialogue, trite as it is."

As Byrd found soon afterwards, supplying scores for films was a surprisingly precarious business. He contacted Cecil in November 1950, lamenting that he was without work. "Unfortunately, the film prospects that I had been promised have all faded away," he wrote, "and in spite of having written hundreds of letters after work, I’ve had no success of any sort. With the exception of the film Tony Draws A Horse I’ve had no work since August 1948, so if you hear of anything, or have too much at once to do perhaps you will kindly remember me."

By September 1954 he had experienced a partial change of fortune, for, in enclosing music cue sheets for Milner’s arrangements, he wrote more positively: "I hope soon to have news of the next series of films, and will contact you as soon as I know the position. I am doing a small film in the meantime, but it is possible that the next series may start in about a month’s time."

Byrd was referring here to the "Douglas Fairbanks Jr Presents" series of TV films, known in America as Rheingold Theatre. Cecil’s incidental music, with Byrd writing for the opening and closing titles, was used for Second Wind, Double Identity, Goodbye Tomorrow, The Heirloom, Rain Forest, One Way Ticket, Four Farewells in Venice and The Last Knife, all completed between February and July 1954, and The Treasure Of Urbano (1955). The last time we encounter Byrd in the Milner archives is his settlement of an account of £104:2:6d in July 1955.

Cecil Milner was also involved in providing short musical cues which lasted only a few seconds, but scoring for films formed only part of his labours. In his hey day he had dealings with all the main music publishers: Chappell, Francis Day & Hunter, Bosworth, Liber-Southern, Boosey & Hawkes, Charles Brull, Berry, Peter Maurice, Keith Prowse, Decca’s Burlington and Palace and several others.

Cecil’s busiest period seems to have been in the late forties and early fifties when he composed and arranged for several mood music libraries. Many of the publishers ran their own record labels - Berry had Conroy, Boosey & Hawkes used the Cavendish name, Harmonic was a Charles Brull label and so on - and the recordings were offered to those film producers, newsreel companies and radio producers who required theme and background music.

Before examining Cecil’s orchestrations and arrangements in more detail, perhaps we should consider the difference between an orchestrator and an arranger, for these words are often freely interspersed.

According to Franck Leprince, there is a significant difference between the two:

"Basically, ‘orchestration’ is the setting out on paper the exact notation of, say, a solo piano part of a given piece, onto separate parts, for a required combination of instruments to perform. Into this, consideration is taken for the range, pitch, number and transposition of each instrument. Ultimately, the instruments are able to reproduce the piece, exactly as the published version, with maybe a little imagination used, to vary the tone colour."

On occasions Cecil performed the duties described above, but, more often than not, he was a top flight arranger. "What an arranger does is far more," continues Franck. "He will literally turn an old piece into a new one, a tired piece into a vibrant one, a sad piece into a happy one. For example, a gifted musician with imagination can turn a song by the Beatles into a piece for a string quartet, sounding as though Haydn had originally written it ... arranging is an art, whereas orchestration is a type of mathematics."

In the British Library collection there are eight Milner printed arrangements which collectively add up to the tip of an iceberg: a Clive Richardson piece Sonia (1943) for Keith Prowse, Reginald King’s Song of Paradise (1946), Where Water-Lilies Dream (1947) and Amourette (1948) for Peter Maurice, Norman Warren’s Brief Interlude (1949), Charles Williams’ Sally Tries the Ballet (1950) and Mai Jones’Rhonda Rhapsody (1951) for Lawrence Wright, and Williams’ well known Sleepy Marionette (1950) for J. R. Lafleur, a subsidiary of Boosey & Hawkes.

Cecil’s connections with Williams remain to be fully explored, but, as we shall show, information from the Milner archive reveals that the two were closely linked. Originally Isaac Cozerbreit of Polish extraction, Charles (Charlie) Williams was a conductor and composer who worked on the first British sound movie in 1929, Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail. He began work for Chappell’s music library at EMI’s Abbey Road in 1942, and one of his earliest recordings, Cecil’s Russian Marching Song (1942), was made there with the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra. Williams and the QHLO also recorded Cecil’sCloud Drifts, a short two minute piece originally written in 1943, the longer Saluting Base, recently revived in Guild Light Music’s GLCD 5140, and Pastoral, Drama, Romance and Naval, all brief play-ins and play-outs lasting from 12 to 22 seconds.

We know of several Milner arrangements recorded by Williams, among them Rendez-vous (1944) Manuel Ponce’s Estrellita, and Circus Parade, Orderly Sergeant and Commentator’s March (all from 1950). Cecil also scored Mantovani’s Gipsy Legend (1952), which Williams recorded, receiving £15 from Lawrence Wright for his troubles, which was the going rate for a score of this type. Also arranged for Wright was Rhonda Rhapsody, recorded by Williams on 31 October 1951. Earlier, Cecil made a special arrangement of Love Steals Your Heart for a QHLO broadcast in 1945, and no doubt there were several others.

A collaboration of sorts materialised in May 1947 when Cecil arranged Williams’ musical spectacleTransport Cavalcade (words by L. du Garde Peach) which celebrated the Jubilee of the Transport & General Workers Union. It was performed at London’s Scala Theatre over a two week period, with Cecil even helping to audition some of the artistes who appeared in the show. He was paid the considerable sum of £188,2/6d for his endeavours. The grateful organiser Edward Genn wrote to Cecil from Transport House: "You certainly seem to have had a very big job in scoring the music for the above event. I had no idea it was going to run into so many pages - it seems to me like a young Grand Opera".

In September 1949 Cecil received a Bosworth cheque for preparing five unspecified Williams works. He arranged the Williams’ compositions Starlings (1945), and Model Railway and Prairie Rider (both 1950), and for the former he received £15:12:6d; for the latter it was a payment of £16:5:0d. Both were recorded by Lafleur with the New Concert Orchestra under Jack Leon.

Milner worked, too, with Williams on the film While I Live in 1947, which produced the famous mini-concerto The Dream Of Olwen, and later prepared this classic melody for the music publishers Lawrence Wright in 1950. In June 1948 he received £86:5:0d from Edward Dryhurst Productions for orchestral scoring for the film Noose, written by Williams and Dryhurst, and was paid for his part in the ensuing Columbia recordings. In 1949 he arranged The Laughing Violin, which is probably the arrangement used by Charles Williams in his recording featuring Reg Leopold on solo violin.

For Harefield Productions in 1950-51 Cecil scored portions of Williams’ music for the film Flesh and Blood, and its main theme Throughout the Years was recorded by Columbia. Another title arranged by Milner for Chappell and Williams was Beggar’s Theme from Last Holiday, also recorded on Columbia. Williams’ The Falcons (scored by Cecil for Lawrence Wright) and Thrill of the Curtain appeared on disc, the latter by the Melodi Light Orchestra.

Other titles that Williams produced, probably using Cecil’s scores, were Quebec Concerto (1949) andRomantic Rhapsody (1952). For unidentified titles recorded by Williams for Columbia on 28 August 1951 Milner received a payment of £71:17:6d, which implies quite a lot of arranging. In 1952 Cecil prepared some short fanfares for Williams, using trumpet and organ, and in December of that year came up with some special arrangements for his Columbia recordings at Abbey Road. He also scoredLong Live Elizabeth and Yeomen of England, made by Williams for Columbia. In 1954 he was still working for Williams, for Columbia paid out £95 to him for unspecified work on 26 November and 16 December. No doubt Cecil arranged more scores for Williams that we are still unaware of, for, asJournal Into Melody readers will attest, this particular conductor-composer had a prodigious output.

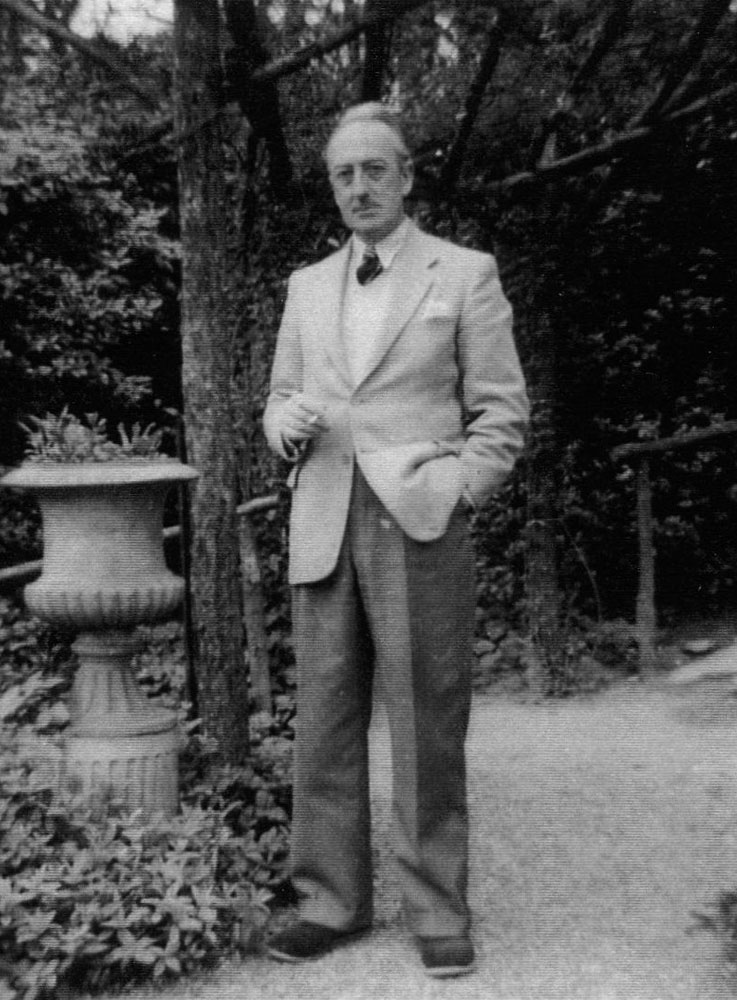

By the late 1930s Cecil was living in West Wickham, near Bromley, Kent. His home was at Hazlehurst, 33 Wood Lodge Lane, where he resided until his death in 1989. The locals would comment, "here comes the composer," as he walked into the shops at West Wickham. One of the principal features of his well-kept garden - where he loved cultivating flowers - was an elaborate fish pond that had three tiers with a bridge going over the top and water cascading underneath!

In 1953 Cecil and Phyllis were divorced and he never remarried, although he had a close relationship with Francesca Gray which lasted many years. It was Francesca who stimulated his interest in antiques, leading to the possession of several Dutch oils. He did much of his composing at the other family home in St Margaret’s Bay near Dover, finding quiet seclusion, unique views across the straits of Dover and splendid walks along the white cliffs with his dogs. He took many photographs of the south coast forelands and quiet Kent villages and had some of his work published in Amateur Photographer of 6 January 1937 (price three pence!) with an accompanying article. At home he had a dark room where he developed his own photographs.

Among Cecil’s earliest non-film music compositions were the incidental numbers Charlotte and Emily for Alfred Sangster’s play The Brontes, originally produced at London’s Royalty Theatre. They were played by Reginald King in a 1936 BBC radio programme. A trawl of the Milner archive reveals that he was kept occupied during the War with many assignations besides film work. In October 1941 he was invited by the BBC (from an address in Evesham) to arrange the Boccherini Minuet for its Casino Orchestra conducted by Rae Jenkins. Another score he provided for the same orchestra was My Old Dutch in January 1942. For Chappell in the same year, he worked on Song of the Bow, Wonderful World of Romance, The Little Irish Girl, Sink Sink Red Sun, Tomorrow, The Venetian Song and Trees.

In partnership with Clive Richardson, Cecil wrote additional music for the radio adaptations of the films Ziegfeld Girl and Sis Hopkins in 1942. In October 1944 he received £70 for work on the public relations film Some Like It Rough, which he and Clive orchestrated together. Another collaboration came on a similar film, Down At The Local. During the summer of 1943 Cecil concluded a special orchestration of Pale Hands I Loved (Kashmiri Song), also a Mikado Selection for the BBC. In 1944 there were arrangements of Richard Addinseli’s Tune In G for Keith Prowse and Paul Lincke’s The Glow Worm for Hawkes & Son.

The following summer both Cecil and Cedric King Palmer were busy helping with arrangements for Concert Productions of Dean Street in Soho. In February 1945 Cecil billed Chappell for £96:5:0d for scoring Highland Lament, Pine Forest, Starlings, Highland Mist, Highland Welcome and Searchlight and several lesser titles, among them Siamese Cat, Fog Scene and Resistance.

Among other post-war commitments there was a special arrangement of I Cover The Waterfront for the BBC’s Majestic Orchestra in August 1945, and a new scoring of Greensleeves for Boosey & Hawkes and Jay Wilbur who recorded and broadcast it in January 1946. In October 1947 Cecil scored parts for HMV’s King Wenceslas, and there was payment, too, in January 1948 for his work on The Toad Comes Home from Wind In The Willows, a recording that was made in America. One of Cecil’s major contributions to light music has recently come to light, this being his arrangement of Vivian Ellis’ Coronation Scot for Chappell’s mood music library (No. 424 in their orchestral works series). Until recently, it had always been assumed that the original arrangement was the work of Sidney Torch, who made the famous Columbia 78 with the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra in 1948 when it was used as the theme for the Paul Temple radio series. But it was Charles Williams who conducted the QHLO for the very first recording on C275 in 1946, although Torch later recorded a new version with his own orchestra for Parlophone in 1952.

Of Cecil’s other arranging credits in the late forties and early fifties we will mention but a few: Royal Lady (1953) for Lawrence Wright, and numerous titles for Chappell including The Brabazon, Late Night Final, Said the Bells, They Ride by Night, Battleship Grey and Shadow of War (all 1950), Skyline(Theme from Rhapsody), The Young Ballerina, Happy-Go-Lucky and The Good Earth (all 1951), High Adventure, General Inspection, I Name This Ship and Birdcage Walk (all 1952) and Proud Capital(1953).

One of the well known names emerging from Cecil’s correspondence is that of pianist Billy Mayerl, who, in discussing an arrangement he was seeking in February 1945, took a swipe at the "lying Dutchman". The object of his vitriol was the shrewd, cost-conscious Dutch general manager of Keith Prowse! With him in mind he pithily observed, "Publishers are all the same. I have fought with them for over 20 years and have yet to find one who accepts the fact that composers and arrangers eat as well as they do!"

After Cecil’s score eventually arrived, Mayerl wrote from Bournemouth, "I’m simply delighted with it, just everything I wanted, nothing I did not want and it is singularly free from mistakes. Just a C# missing in the flute part in bar 20, that’s all I had to correct. No, there is nothing I wish altered, toned down or strengthened. I am terribly pleased with it." Billy even thought that Cecil’s bill for £22 was too low and rounded it up to £25!

Writing to Cecil again some eight years later about a title earmarked for Charles Williams, Mayerl wrote whimsically: "I have just completed another ‘piece of nonsense’, a rather fastish novelty type and after Charles Williams’ comments on my orchestrations, I feel perhaps I ought to give it to you to score! When I see you, I will play it at you and you can tell me whether it is orchestral or not."

As already revealed, Cecil was on very friendly terms with the composer-arranger Clive Richardson, who was a great friend of his family and godfather to Timothy Milner. Clive’s first wife Eileen often went on holiday with Cecil’s wife Phyllis while the two composer-arrangers stayed at home working. Three and a half years younger than Cecil, Clive also studied at the Royal Academy of Music, in particular violin, clarinet, trumpet, trombone and timpani. Like Cecil he was an all-rounder, at one time the travelling accompanist to the cabaret singer Hildegarde, on other occasions involved with the Gaumont British Films set-up in the late 1930s.

Richardson was a giant of a man, standing 6 feet 9 inches, who was a born raconteur with a remarkable memory. His conversation was invariably entertaining, but on one occasion he disclosed to Timothy Milner how envious he was of Cecil; after all, having access to his family’s private means, he - unlike Clive - did not have to work for a living, and there was also his regular work with Mantovani. Nevertheless, they were great comrades and Clive often spent his holidays at the Milner holiday home near Dover and visited the family homes in Wimbledon and Poole. A note from Clive to Cecil in settlement of an account in March 1955 reveals how close they were: "The score came out very well and I was, as usual, very impressed with your orchestral treatment as was everybody else. My only regret was that your lumbago prevented you from coming along as we should have all very much liked you to have been there with us." As if to underline their friendship, the note was affectionately signed off in French, "Toujours a toi" and "Meilleurs amities." In earlier times Cecil did several arrangements for Clive and the Lawrence Wright company including Prelude to a Dream(1950). It was Clive who was one of Cecil’s seconders when he was accepted into the Savage Club on 6 November 1947. Proposed by Billy Mayerl, his other supporters included the violinist Edward Stanelli and musicians Charlie Williams, Tony Lowry and Charles Shadwell. Clive himself had been a member of this club for the arts and music since 1944, two years after Mantovani was accepted. Norman O’Neill, Cecil’s late tutor, was a member, too, before his untimely death, and Cedric King Palmer, another of Cecil’s musical friends, eventually joined in 1961.

Between 1946 and 1950 some of Milner’s own compositions were given air time by Gilbert Vinter and the Midland Light Orchestra. Flags in the Square, which first appeared in a Light Programme show in December 1946, was formerly known as Road To Victory in 1943; the name change occurred after its acceptance for publication by Bosworth in October 1944. In thanking Vinter, Milner informed him that "a rather sugary piece" called Lovelorn Lady might be of interest to him, and the conductor duly obliged with a broadcast in February 1947. The melody was recorded by the Regent Classic Orchestra for the Bosworth music library.

Cecil wrote to Vinter in March 1948 concerning one of his pieces for Harmonic Music:

"The publishers like the tune and want to get out a commercial arrangement but I would first like to have a good broadcast with a proper combination such as yours." Including detailed notes on how the opus should be tackled, Cecil was anxious that Paris Fashions should be played "rather languidly". It was first broadcast by the Midland Light Orchestra a couple of months later.

When Cecil revealed that he had created a new arrangement for Boosey and Hawkes titledFantasietta on Greensleeves, Vinter, asking for it to be sent along, commented that "I think it is probably time that we had something to replace the beautiful, but eternal Vaughan Williams." The piece was used in the film Lakeland Story and was conducted by Charles Groves, the conductor of the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra, at the Winter Gardens in Bournemouth. Milner’s Trysting Place was also broadcast by Vinter in Music for Teatime in September 1949.

In January 1950 Cecil commended Vinter to his pastoral allegretto, Primrose Dell, "a rather cheerful tune which comes off quite well in a record that has just been made." This delightfully melodic piece, recorded by the Harmonic Orchestra under Hans May, has happily resurfaced in Guild Light Music’s GLCD 5112. Another piece from 1950, Playground, assigned to Chappell in July, was included by Vinter in the radio programme Morning Music in March 1951.

Other compositions were written as "interlude music" including Downland, used once in a ploughing sequence. Assigned to Chappell in March 1950, it was recorded in Luxembourg by L’Orchestre de Concert under Paul O’Henry and recently appeared in the Living Era Twilight Memories compilation (CD AJA 5419). in the early 1950s Downland was often used in minor American TV productions with other pieces composed by Cecil such as Lovelorn Lady, Pastorale, Primrose Dell, Abbey Ceremony, Tiysting Place, Paris Fashions and Cloud Drifts.

Midsummer Gladness, assigned to Charles Brull in March 1955, was recorded by the Symphonia Orchestra under Ludo Phillip and has appeared in Guild Light Music’s compilation GLCD 5138, as has the Milner arrangement of Charles Wakefield Cadman’s I Hear a Thrush at Eventide, recorded by the New Concert Orchestra under Jay Wilbur (GLCD 5143).

Additionally, the titles Classic Event (from 1949), Ringmaster and In Line Ahead (1950) and Men At Work (1951) have been listed by Boosey & Hawkes in three archive compilations drawn from the Cavendish label. Such titles were often in demand for newsreels and documentaries, as shown in Cecil’s royalty statements from the early 1950s. As far as we are aware, many of Cecil’s other compositions which appear on music library recordings are awaiting re-discovery. Our knowledge is incomplete, but we know that Air Lift (from 1951, re-titled Fly Past in 1952) and State Drive (also from 1951) were recorded by the Melodi Light Orchestra for Chappell. Then there were the recordings ofPlayground (1950) by the New Concert Orchestra (Cavendish), Sea Power (1947) by the New Century Orchestra (Francis Day & Hunter) and the "shortie" Mounting Tension (1952) by the Continental Theatre Orchestra (Bosworth). Shadow on The Blind (1949), Angry Mob, Gun Man, and Sunlit Fields(from 1950), Vigil, Smash and Grab (1951) and Resolute Avenger (1952), all pieces lasting about a minute and a half, and the play-ins/outs Frolic and Screen Pageantry were recorded by the International Radio Orchestra, again for Bosworth.

For Harmonic’s music library (later Charles Brull Ltd), Cecil wrote other short compositions such asTragic Desolation and Power Plant, assigned in October 1951, and Ticker Tape and Piston Rod, from March 1952, each lasting just over a minute. Lido and the full length Melody for Lovers were recorded in Paris in October 1953, but Cecil was unable to attend the recording.

Others written for Charles Brull include Abbey Ceremony (1950), Windsor Greys (1954), Department Store (1956), Amnesia and Wide Horizon (1957), Gracious Queen (1958), Summit Meeting andChildren and Animals (1960), Le Mans, Comedy Team, Caxton Hall, Pioneers and Show Place (1961), and Romantic Vista (1963). As was usual, Harmonic/Brull and Milner shared the performance and broadcasting fees with the composer receiving additional sheet music publication payments, the proceeds from sound films and mechanical rights as well. A similar arrangement operated with Bosworth and others. In the summer of 1952, Charles Brull, the Czech born managing director of the company which bore his name, died while on a business trip, but the business continued and is still represented to this day in Berlin.

For Frances, Day & Hunter Milner composed Solemn Moment (1947) and Coat of Arms and Lowland Stream (assigned in June 1952). For Berry and the Conroy record library he wrote Master Mariner,Rescue, Mechanical Handling, Teleprinter, Air News and Blaze of Brass (a series of short fanfares) in 1959. Others for Chappell include Pursuit and Aerial Activity from 1943 and Shipwreck (1948).

In the early 1950s Cecil began scoring for Mantovani, whose career had taken off after Ronald Binge’s arrangement of Charmaine had become a roaring success in America. After Binge’s departure in 1952, Monty looked around and took stock, before asking Cecil to join him, possibly on a casual basis at first.

Cecil may have first encountered him through the Savage Club, but there is some evidence that they had tenuous contact as early as July 1952 when Cecil began arranging Monty’s composition Gipsy Legend for Charles Williams through Bill Ward, the general manager of Lawrence Wright. A revised commercial score was finalised for Wright in October of that year, after it had been recorded by Williams.

By now well known in music circles, Cecil probably felt that he was privileged to join Mantovani, as this would help keep him in full employment. Their first collaboration was the eventual million sellingStrauss Waltzes album in September 1952. Cecil was paid the healthy sum of £119 by Monty for his scores and had no further claim on them, except for performance rights.

Mantovani later assigned and transferred the 14 non-copyright waltz arrangements to Decca for a fee of £303:2:6d. Through no fault of Mantovani, Cecil later found that he was not receiving any royalty payments for seven of the pieces he had arranged: Artist’s Life, Roses from the South, Wine, Women and Song, Morning Papers, A Thousand and One Nights, Vienna Blood and Accelerations Waltz. He raised the matter with the Performing Rights Society in November 1953 and after much correspondence began to receive royalties for his work. This episode serves as a good example of how Cecil kept a very close eye on his royalty payments; after all, they were his bread and butter.

At first Mantovani turned to Cecil for orchestrations of light classical pieces or Christmas songs such as Joy to the World, Nazareth and O Little Town of Bethlehem. He was duly paid £75 by Decca for these scores. There was a fine arrangement, too, of Delibes’ Waltz from Naïla, recorded with pianist Stanley Black in February 1953, earning Cecil a payment of £16:10:0d from Decca.

In the early fifties, Monty, with an eye on the American market where he was selling albums galore, set about recording suites of songs by the leading operetta composers Victor Herbert, Sigmund Romberg and Rudolf Friml. In due course Cecil contributed ten of the arrangements, among them such perennial favourites as I’m Falling in Love with Someone, A Kiss in the Dark, Serenade from The Student Prince, Deep in My Heart, Song of the Vagabonds and Only a Rose.

In 1955 Mantovani invited Cecil to come up with five more arrangements for a Favourite Melodies from the Operas album. A year later there were four more scores for An Album of Ballet Melodies, for which Cecil received a fee of £167:16:6d from Decca, a substantial amount in those days. For his last mono album, The World’s Favourite Love Songs (1957), Cecil expertly arranged You Are My Heart’s Delight, My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose, Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes, Ich Liebe Dich and For You Alone.

Later that year he prepared Strauss’ Perpetuum Mobile and Chaminade’s Autumn for a Concert Encores LP, then made one of his first "popular’ song arrangements for Mantovani, this being the movie opus An Affair to Remember. In between times, he helped out on scores for Monty’s television shows.

Even so, he did not stop working in other directions. From time to time he helped out the BBC’s Majestic Orchestra, such as in late 1949 and early 1950 with scores for Novello’s Some Day My Heart Will Awake, Boulanger’s Avant de Mourir (My Prayer) and Darewski’s If You Could Care. There was some routine work for bandleader Philip Green in 1952 before a letter in February 1953 from composer Donald Phillips of Skyscraper Fantasy fame confirmed Cecil’s arrangement of his Bathing Beauty Waltz, for which Lawrence Wright paid out £18:17:6d. There were orchestrations, too, for EMI 12 inch 78s, such as Novello’s Dancing Years and Glamorous Nights. In January 1955 Milner worked on a new arrangement of Osmar Maderna’s Cavalcade of Stars for a New Majestic Orchestra broadcast. Some scores for Charles Brull followed in 1955 and 1956, prompting a letter from the company asking for brief notes on his life for publicity purposes.

In May 1956 Cecil received a message from his friend Cedric King Palmer expressing concern about the small fees background music was attracting on television. It suggested that a joint appeal might cause the Performing Rights Society to revise its system of allocating points which was penalising composers of such music. We learn from this letter that Ronald Hanmer, Hans May, Palmer himself and others had already taken up the cudgels.

A letter from veteran light music composer Reginald King in March 1959 was most complimentary. ‘Very many thanks indeed for your letter and the score of my new tune, which arrived by the same post from Eric Adams. I feel delighted with it from every aspect, particularly the way in which you have so skilfully distributed the woodwind and yet at the same time leaving the melody complete on the strings where required."

A less welcome letter from the Berry music company came through the post in April 1962. Revising the allocation of mechanical fees for works in the Conroy library, it advised Cecil that the publisher would now receive 70% of the fees and the composer 30%, instead of the usual 50-50 split. Berry gave its reasons as increased costs in production and promotion in the international field. When music publishers Charles Brull wrote to Cecil at the beginning of May to propose the same percentages, it quoted the ever increasing costs incurred by the company in producing its library and the difficulties of competing on equal terms with those foreign mood music libraries which were exploited both here and abroad. It was perhaps an indication that the golden era of the mood music composer-arranger was over.

Between 1952 and 1974 Cecil scored over 250 pieces of music for Mantovani, some of these the more expansive classical interpretations he required, but others definitely more popular in style. Nevertheless, the brilliant Roland Shaw was always available to score the more contemporary songs that required a touch of taste. By 1958 Mantovani was making more use of Cecil’s talents, requiring him to factor his skills on several more "popular" titles. For the Continental Encores album Milner prepared a major version of Autumn Leaves and in More Mantovani Film Encores the delightfulWhatever Will Be, Will Be (Que Sera Sera) was a triumph. Surprisingly, Monty rarely used Milner’s composing talents, which was a pity. There were the tour curtain raisers Gala Night (1966), renamedMasquerade, and Night Out (1970), but that was about all except for The Frightened Ghost, andPercussion on Parade (1960) written to show off the skills of percussionist Charlie Botterill. Unfortunately, none of these concert pieces was ever recorded.

Relations with Monty were invariably cordial and there was a fine business friendship between the two men. As proof of this, Monty once signed a record brochure, "to Cecil with my grateful thanks for your very fine work." Apart from making music together they had a shared interest in cameras and often compared photographs. At Christmas there were warm exchanges, there were letters and holiday postcards, too, and more than once Cecil was invited down to the Mantovani home at Branksome Park in Poole, Dorset.As revealed in Mantovani’s biography, the late Tony D’Amato, Mantovani’s record producer, remembered Cecil with great affection. "Always a welcome sight was the shy and ultra-reserved Cecil Milner, Mantovani’s mainstay arranger and orchestrator who arrived at Decca studios like a country squire on an outing to the big city," he recalled. "Harris tweed jacket with toggle buttons and leather-reinforced elbow patches at the sleeve, peering through the thickest glasses, Cecil resembled not so much a music arranger as he did a game warden."

By now at the height of his powers, Cecil contributed seven titles to the American Scene album recorded in January and June 1959. The sheer bravura of Turkey In the Straw and a colourful interpretation of Yellow Rose of Texas were combined with some lovely arrangements of songs by Stephen Foster. On another worthy album, Songs to Remember, Cecil was entrusted with the grand sounding Blue Star, also Tonight from West Side Story, as well as A Very Precious Love and Vaya con Dios. For Operetta Memories he delivered five beautiful arrangements, among them the FrasquitaSerenade and the Waltz from The Gipsy Princess.

The following year both Mantovani and Milner pooled their arranging talents to deal with a large recording schedule of show and film tunes such as Shall We Dance from The King and I, theSundowners theme and show songs of the calibre of Mr Wonderful and I Feel Pretty. Cecil also found the time to arrange The Carousel Waltz, Ascot Gavotte, A Trumpeter’s Lullaby and Seventy-SixTrombones. When Mantovani brought out his Italia Mia LP in February 1961, Cecil was well and truly let off the leash. Much of this beautiful album was drawn from the light classics, which gave Milner the opportunity to score seven titles, including the traditional Variations on Carnival of Venice which ends with a delightful fugue and Tchaikovsky’s Theme from Capriccio Italien. In the latter the theme was played as originally envisaged as a slow, warm sentimental melody, then as a re-scored rousing piece. Unusually, Monty also entrusted Cecil to make an arrangement of his own lovely opus Italia Mia.

Throughout the sixties and into the seventies Mantovani, who was always very busy, had to rely greatly on first rate material from Cecil and his other main arranger Roland Shaw. In this short article it would be inappropriate to provide an exhaustive list of Cecil’s achievements, but we should at least recall some of the highlights. For Songs of Praise (1961) he arranged ten of the 14 titles includingAbide with Me, Eternal Father and a wonderfully stirring version of Onward Christian Soldiers, recorded with the Mike Sammes choir and an augmented orchestra in Kingsway Hall, Holborn. There were six Milner arrangements for American Waltzes in 1962, four more in Classical Encores including the vibrant Hungarian Dance No 5, and the superb Oliver! suite scored for an American issue.

In the same year Cecil contributed his memorable arrangement of The Big Country and his dramatic reworking of Charles Williams’ Jealous Lover, both for the Great Films - Great Themes LP. He was also main arranger of Mantovani’s album with the tenor Mario del Monaco. For A Song for Christmas in 1963 Cecil scored seven titles including O Thou That Tellest Good Tidings, recorded with the orchestra and organist Harold Smart at Kingsway Hall. Normally a choral work, this magnificent four and a half minute extract from Handel’s Messiah remains one of the highlights of Mantovani’s - and Milner’s - career.

The Mantovani/Manhattan album in 1963 brought forth the dramatic Slaughter on Tenth Avenue and the lovely The Belle of New York among others, also Milner’s novel interpretation of Take the A Train. The Ellington/Strayhorn classic was originally written to chart the progress of a New York subway train that fizzed from Manhattan to Harlem, but Milner, himself a steam train enthusiast and supporter of the Bluebell Railway in Sussex, conceived the song as something quite different. Where Ellington swung, Milner chugged! His refreshing score painted a picture of a much more sedate steam train, causing some mirth behind the scenes. When Tony D’Amato protested to Monty in good humour that New York had not seen that sort of train in 50 years, Monty responded with a smile, "This is what comes of going about only by taxi!"

In 1964 there were two substantial Milner medleys in Folk Songs Around The World and a captivating look at Catch a Falling Star which set the Incomparable Mantovani album alight. In 1965 he wrote six arrangements for The Mantovani Sound and eight for Mantovani Ole, including Fiddler on The Roof, Spanish Gypsy Dance and Mexican Hat Dance. In the Mantovani Magic album which celebrated Monty’s 25 years at Decca in 1966, Cecil’s arrangements of I Wish You Love and Stardust stood out.

For later albums he excelled with the likes of Ben Hur, What Now My Love, My Cup Runneth Over, Hora Staccato, Gypsy Carnival, the Gypsy Dance from Carmen, If I Were a Rich Man, Theme fromThe Virginian, the Elvira Madigan Theme, I Will Wait For You, A Lovely Way to Spend An Evening, Isn’t It Romantic and many more. We should not forget, too, a delightful scoring of the old favourite When the Lilac Blooms Again for an album issued in German speaking countries and Australia, and those three lovely arrangements, using a chorus, of What a Wonderful World, Sunrise Sunset and You’ll Never Walk Alone for Mantovani Memories. In short, when working with Mantovani Cecil Milner never lost his touch.

During the late 1960s guitarist Ivor Mairants interviewed Mantovani for a guitar magazine. On being asked how he and Cecil agreed on the titles that contained guitar solos, Monty told Mairants that Milner’s "great worry is, of course, that as an orchestrator, he understands the guitar extremely well and as such likes to feature the guitar in its full capacity as a solo instrument. When guitars are featured in that way they have a character all of their own and give a piece a certain touch which only that particular instrument can give, and he selects what I think are very suitable passages in the score for the guitars."

Mantovani continued, "Sometimes he’s a bit naughty with it and makes it technically difficult; he forgets that not all guitarists are such experts and, therefore, we have to take a bit of time in the recording studios so that the poor guitar player can have a go at it’, as we call it." Nevertheless, Monty concluded, one would find that most recordings had come out extremely well.

Correspondence between Monty and Cecil is sparse, mainly because they would have contacted each other by telephone, but in two late communications that have survived, Monty demonstrated his complete confidence in his long-time arranger. In one note he wrote, "Just mark what type of rhythm you want, and let the drummer work on it. This is what everyone does today, which saves a lot of thinking!" In another he commented, "Here are your last two titles which are quite good for a change and will give you some scope for orchestration. Please do them in any way you want, not to worry about rhythms if they should not fit your ideas." Sometimes in Mantovani’s concert programmes Milner had the lion’s share of the arrangements. The most notable example was on the 1970 British tour when there were 15 of his scores in the 22 titles, among them the concert opener Night Out. Special concert arrangements he made down the years include a Fantasy on Brahms Airs, prepared with violinist David McCallum for the 1963 British and American tours, Fantasy on Nautical Airs andThe Heart of Tchaikovsky, both from 1967, the Irish Washerwoman (1968) and a pot-pourri of show themes, Broadway Scene, from 1971.

During the sixties and seventies Monty’s tour-ending concerts at the Royal Festival Hall were always special occasions. After one of them, Timothy Milner tried to gain entry to the "green room" with his girl-friend, but was barred by Mantovani’s ever- zealous manager, George Elrick, who, having thought they were autograph hunters, sent them packing! Fortunately, when the mistake was realised, a messenger ran after the chastened couple to invite them back for the hospitality they had been hoping to receive as guests of Cecil Milner!

Throughout those golden years Cecil earned decent royalties from Decca’s publishing arm, Palace Music. These ranged from £1,261 in 1967 and £1,102 in 1969 to £1,154 and £1,063 for six monthly periods in 1971 and 1972. 1973 was a particularly good year, for up to 30 September Cecil was paid £3,207. After Mantovani retired in 1975, Cecil wound down his activities as a composer and arranger. His good friend Clive Richardson, on the other hand, continued composing until two or three months before he died. Cecil was content, however, to live quietly with his dogs and enjoy his antiques. Royalties from his various activities and income from his own investments ensured that he led a very comfortable existence.

Cecil stopped working at the age of 69, leaving an impressive body of work produced over a period of forty years. Gradually, however, his familiarity with his own music publishers diminished, although royalties were paid out on a regular basis until he died. At various stages he received fees from sources in South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, Belgium, Spain, Japan, Portugal, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and the Philippines. Cecil’s total royalty calculations for the year ending 4 April 1984 show that he earned £4,837, a decent sum of money in those days. In the last year of his life, his total royalties between April 1988 and March 1989 amounted to a relatively healthy £4,601.

After Mantovani died in March 1980 after a long illness, Cecil wrote his own tribute to his friend’s family: "It may perhaps be of some comfort that his many colleagues who enjoyed the great pleasure of Monty’s friendship are sharing your sense of grief. He was universally loved, and I never remember hearing a single derogatory word spoken of him. A fine musician and a fine man."

On 25 November 1989 Cecil died in relative obscurity aged 84, after suffering a heart attack at home in West Wickham. There were just six people who attended his funeral, including Clive Richardson, his second wife Unity and members of the Milner family. Cecil’s arrangements for Mantovani of Onward, Christian Soldiers, Abide With Me and others were played at the funeral service on 8 December when he was laid to rest in a quiet corner of the St Margaret’s-at-Cliffe village churchyard. Although recognition of his worth has been slow in the past 20 years, the name of Cecil Milner has received more prominence in recent times. His earlier work is now emerging in CD compilations and most of his arrangements for Mantovani have appeared in the Vocalion series which has prospered since 2001. On 1 October 2006 Radio 3 presented a concert dedicated to the memory of Humphrey Carpenter, the writer, broadcaster and musician, in which Cecil’s arrangement of Coronation Scot was intriguingly revived by the BBC Concert Orchestra conducted by Ronald Corp. In January 2008 there were ten of Cecil’s arrangements played in the Mantovani gala revival concert at Poole in Dorset.

In conclusion, we feel that Cecil Milner deserves his share of the limelight. While perhaps not one of the leading lights of British 20th century light music - we have in mind Mantovani, Melachrino, Farnon, Goodwin, Torch and Williams and one or two others for that accolade - he was nevertheless a most valued, prolific and versatile member of his profession.

His steadfast work for Mantovani alone would justify such a claim, but deserving of more recognition, too, is his remarkable career elsewhere which we have outlined in this article. Hopefully, more of his compositions and arrangements will be brought out of obscurity to support our belief that he was a substantial force in film and light music.

Sources and acknowledgements:

The Cecil Milner archive - in the possession of Timothy Milner;

Edward Cecil Milner’s student record - Bridget Palmer, assistant librarian, Royal Academy of Music library, special collections and archives, letter of 8 April 2008;

Cecil Milner and Gilbert Vinter correspondence (1946-1952) - BBC Written Archives Centre, Caversham Park, also the Milner archive;

Concerning orchestrators and arrangers - Franck Leprince, e-mail of 25 July 2008;

Norman O’Neill - A life of music by Derek Hudson, Quality Press 1945, pp 120-122;

The guitar and the orchestra: Ivor Mairants asks the questions and Mantovani supplies the answers - extract from BMG Magazine, quoted in Mantovani’s British tour programme, April 1972;

Sir Dan Godfrey Champion of British composers by Stephen Lloyd, Thames Publishing 1995;

Clive Richardson (1909-1998) by David Ades in Journal Into Melody, issue 138, March 1999, pp 6-8;

Clive and Unity Richardson A personal reminiscence by Tony Clayden in Journal Into Melody, issue 138, March 1999, pp 8, 10;

Mantovani - A lifetime in music by Cohn MacKenzie, Melrose Books 2005, pp 147-149 et passim

This article first appeared as a three-part feature in ‘Journal Into Melody’ – the official magazine of The Robert Farnon Society, issues 178 (December 2008), 179 (March 2009) and 180 (June 2009).