(Leslie Clair)

Analysed by Robert Walton

After constantly analysing a great deal of light music in all its diverse forms, it’s always nice to return to the comfort zone of the legendary Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra, rummaging through its archives for more marvels I may have missed. Such is its worldwide reputation, it’s one orchestra always guaranteed to give a perfect performance with state of the art compositions. One such classic is Dance of the Blue Marionettes written by Leslie Clair. His real name was Leslie Judah Solley (1905-1968) who was at one time an MP for the Thurrock constituency of Essex.

Cinema organist Sidney Torch recorded an old-fashioned syncopated version of Dance of the Blue Marionettes in 1933. Fourteen years later in 1947, Torch having reinvented himself as a light orchestral composer, again had a part to play, albeit a smaller one as conductor of the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra. You would have thought Torch was in the ideal position to score it himself but it was not to be. Instead, one of the best backroom boys in the business, Len Stevens, fulfilled that role creating a brilliant makeover of Dance of the Blue Marionettes. In a slower tempo than the original, he gave it the wash and brush up it badly needed. Composer Clair couldn’t have dreamt of the result. Ironically it sounded very much like a Torch arrangement full of invention, crispness and wit. So with that in mind let’s dissect it and investigate the anatomy of a marionette.

Pizzicato strings, flute and muted brass set the scene in an unusually long introduction (12 bars) including a particularly skilful section just before the start. The composition promises to be a great little workout for all concerned. The opening of Dance of the Blue Marionettes is identical to the first two bars of Music, Music, Music, but there the resemblance ends. We continue with that toe-tapping tune completely comfortable and contented in its new clothes. In bar 9 to avoid monotony that same tune is heard in a new key. Then sensitive strings come into their own with 8 bars of gorgeous sweeping brushstrokes acting as an excellent contrast. So back to the familiar strain low lighted with a bass line of sustained strings.

Warm woodwind repeat the strokes in closer harmony but the strings can’t resist the chance to show how it’s really done. The whole thing is then repeated (except the warm woodwind) until we finally reach an imaginative fun-filled coda and Dance of the Blue Marionettes comes to a carefree close.

I can’t think of a better example of a 1930’s tune being transformed so deftly into the 1940s when light music truly came of age and sounding quite at home in its new surroundings. This was an undoubted triumph for boffin Stevens!

Dance of the Blue Marionettes can be heard on “Childhood Memories” on Guild’s Golden Age of Light Music (GLCD 5125).

Differing Versions of the Same Set Light Music Selections - An Update

Written by William ZuckerAn article by William Zucker.

Just a little over two years ago, I wrote an article for the RFS site with the title "Differing Versions of the Same Set Light Music Selections."

Over this time period, I have obtained information that would necessitate my adding additional material, as well as correcting some erroneous assumptions that I had made in the absence of such information.

Much of this that I now have to share has come and is continuing to come from the uploads of Mr. Graham Miles, a fellow RFS member whose channel on YouTube I now subscribe to.

There have been made available a considerable number of recordings that originated in the various mood libraries, not previously available. I in turn have shared many videos from YouTube with Graham, and the exchange of information has become mutually profitable, even though at present, I do not have the ability to upload files whereas with Graham it is a passion - he will even take recordings that I request that he upload if I observe that they have not been uploaded by others, if he happens to have them available. As may be gathered, his collection of light music selections from various sources is considerable, and he does explore other channels offering such music, as I have been myself.

What I would like to embark on here would be to go over my article of January, 2015, and take it point by point to make additions, corrections, and general observations as a result of this additional information I have obtained over this period, throwing in some comments that I feel are pertinent:

With Leroy Anderson, I had mentioned that the earliest versions he had recorded of his selections were in my considered opinion, the best ones, and gave my reasons for this preference, and have even urged any interested listener to consider these when a choice was to be made,

The same, by the way, would apply to the Boston Pops/Arthur Fiedler recordings I had specified; namely, "Serenata, "Sleigh Ride," "Fiddle Faddle," and the Irish Suite. Here too, I would give the palm to the earliest versions. With the Irish Suite, I have noted that all performances by the Boston Pops that have been posted on YouTube are apparently from a live performance, not from the original recording, as there is applause between each movement. Many listeners conceivably might not wish to have this intrusion within the work but would greatly prefer to listen to it uninterruptedly, fine as the rendition itself may be.

David Rose comes under discussion here as well, as Graham has uploaded a later version of "On a Little Country Road in Switzerland," one of Mr. Rose's most endearing selections - actually the two versions were uploaded side by side so that a direct comparison could be made.

In this later version, which I have hitherto remained totally unaware of, unlike the case of the drastic overhaul with "Gay Spirits" and the major touchups with "Holiday for Strings," in this case the composition remained essentially unchanged, save for the elimination of the charming yodeling effect that appears at the beginning and end of the piece. One might well ask why Mr. Rose saw fit to eliminate this when it so beautifully sets off the piece in its original version. The overall instrumentation is somewhat heavier as well, whereas a light touch is clearly needed in this piece.

Which brings me to Percy Faith, whose work along these lines is a subject in itself.

Quite recently, I became aware of the fact that when Mr. Faith was contracted to make recordings for Columbia, he expressed a lack of interest in working with soloists in his recordings, whether vocal or instrumental. The deal was made sweeter for him when he was advised that he would only need to cut a few recordings with soloists, and with all the rest of these he could produce as he wished. This disinclination and lack of interest I refer to unfortunately evidenced itself in his recordings, and it potentially represents a side of him that I could well imagine that his admirers would choose to overlook and forgive.

In one or two of the recordings he made with a soloist, his accompaniment in itself was so flamboyant (think of "Rags to Riches" he made with Tony Bennett as an example) as to threaten to steal the attention from the soloist who quite properly should be in the foreground. In them, Mr. Faith sounds almost like a caged animal fighting to break the bonds of his imposed limitations.

This had other manifestations in that a number of recordings that he did make with a soloist or soloists, he felt that he actually had to go back and rerecord these totally on his own, and one can only speculate on the need for this.

Thus we have his classic hit with Felicia Sanders of Auric's "Song from Moulin Rouge," although here at least in his later instrumental version he gave us an expanded double length version which did not occur elsewhere in these instances. We have the song "Non Dimenticar" which he originally recorded with Jerry Vale, which recording made the charts, but then he immediately went back to record a nearly identical version musically, entirely on his own, without the vocal line.

Two of the most enchantingly beautiful settings he recorded was with a wordless chorus dubbed "The Magic Voices" featured in "Zez Confrey's "Dizzy Fingers" and Rodgers' "If I Loved You" from "Carousel;" both really lovely settings I still listen to with pleasure today, and then for whatever reason he had to go back and redo both of these selections without the wordless chorus, and without the charm of the original, to dubious purpose.

And I already mentioned the selections from his album "Music Until Midnight" which featured Mitch Miller as oboe/cor anglais soloist, which was one of the most successful albums of mood music ever made, and then Mr. Faith right afterward had to rerecord many of the selections from this album without the wind solos, with a corresponding loss of shape and focus in the way the selections now presented themselves.

One may well ask, why did he feel the need to rerecord so many selections that he did with featured soloists over again without them? Was the matter of working with soloists so disagreeable to him for whatever reason that he felt the need to "cleanse" them in some way? I do not have a clue as to the reason for what unmistakably took place, and knowing the circumstances under which he signed his contract with Columbia records, I can only say that it is perhaps kindest to overlook this facet of his work as not entirely complimentary to him, as he was a truly great artist in this genre, so perhaps we should allow him some slack as he has overall more than earned our admiration for his accomplishments. But one could also point out the numerous remakes even of outstanding instrumental selections from his earlier years, which prompts me here too to advise people to stick with the earlier versions as much better showing off the genius in his settings, as against the cheapening and coarsening of his work in their later incarnations, probably in the interests of commercialization, although in that regard he was not alone in this field, as has been pointed out.

* * *

The situation with the recordings from the UK, notably those that originated in the various mood libraries, remains as confusing as ever. Often a piece was recorded more than once by the same conductor, producing two different versions, although in most cases I indicate a preference for the composer's own original versions, with the exceptions as I have noted in the article, but with the additional information I have received from viewing Graham's uploads, questions still abound. I find dealing with this to put things in their proper places as inordinately challenging, and for the moment I don't know where to begin.

Take "Portrait of a Flirt," for example. Robert Farnon's first recording of the piece with his own orchestra (the best, in my opinion) has appeared in the market with the orchestra designated as "his orchestra," the "New Promenade Orchestra," and the "Kingsway Symphony Orchestra." I couldn't at this point state which is correct, but the fact remains that they are the self-same identical recording, not to be confused with a later one he made of the same piece. There are also two recordings by the Queen's Hall Light Orchestra, stated as being conducted by Robert Farnon and by Sidney Torch as given to us. These are two noticeably different recordings, neither of which I give a recommendation to, for various reasons. Of course, I am not taking into account the version by David Rose which in my opinion is a distortion, and I will not include it for purposes of this discussion.

I raised the question as to whether Sidney Torch conducted two different recordings of Haydn Wood's "Wellington Barracks," distinguishable to me by the final cadence at the end, and have finally established that such was indeed the case, but would then raise the question as to why the rerecording was even necessary. (Incidentally, the longer version of Wood's "Soliloquy" I referred to in my article was performed by the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, probably under Adrian Leaper, but as I had stated, I greatly prefer the shorter version with the Queen's Hall Light Orchestra conducted by Robert Farnon.)

I stated in my article "pieces by Felton Rapley and by Peter Yorke, as performed by the Queen's Hall Light Orchestra and by these composers conducting their own orchestras," or words to that effect. This was a natural assumption made in the absence of complete information. As it turns out, Felton Rapley was not a conductor and did not conduct any of his pieces - he was an organist and pianist. Peter Yorke did lead an orchestra of his own, but actually recorded very few of his own pieces. Most of these were done by Robert Farnon or Sidney Torch with the Queen's Hall Light Orchestra, although the former recorded some of these with the Danish Radio Orchestra under an assumed name due to a musicians' strike occurring at the time these recordings were made. Other Yorke selections, rather interestingly, were recorded by Dolf van der Linden, who frequently crossed over into this repertoire by the composers who wrote for the various British mood music libraries, a rather interesting combination of talents in this case.

With "Spring Cruise" by Peter Yorke, a very confusing situation exists in regard to the genesis of the recording. I have long known this piece as the final number in an album by the Queen's Hall Light Orchestra (no conductor's name given) entitled "Very Very Dry," released in the USA in the mid-1950's. I next came across it on YouTube in an uploaded album of Peter Yorke selections entitled "Melody of the Stars." In an album put together in that manner, I reasonably assumed that the aggregate of all Yorke selections was conducted by Peter Yorke himself. Most recently, Graham has uploaded a recording from his collection of this piece as performed by the "Melodi Light Orchestra" as conducted by "Ole Jensen" which was the nom de disc for the Danish Radio Orchestra under Robert Farnon during the musician's strike concurrently taking place. The point that I am making here is that all of these recordings that I am enumerating of Peter Yorke's "Spring Cruise" are the identical performance - there is no discernable difference between them. Which designation, then, should we go by, and what actually took place in the preparation of these recordings - what is the actual truth of what had occurred here?

Similarly, a selection entitled "Pizzicato Boogie" by Jerek Centeno, appearing in an album conducted by Dolf van der Linden (recording under the name "Van Lynn") in an LP album entitled "Escape" on the American Decca label, also appeared in an EP set entitled "Dutch Treat" featuring what is dubbed the "Hilversum Orchestra" on the "X" label, which appears to have been an offshoot of RCA Victor, judging by the graphics on the label. The two recordings are identical; they are the same rendition. Both of these cases I bring up can be very confusing to individuals attempting to determine the actual genesis of a recording.

There is a video posted on YouTube of Acquaviva's performance of Bob Haymes' "Curtain Time," claiming to be an "original version" as distinct from the recording on MGM records that was commercially available for many years and which is also posted, but upon listening to this alleged "original version" I could find absolutely no difference from the version commercially available and will assume that it is the very same rendition.

Oftentimes, when a recording appearing on a 78/45 RPM single was taken over into an LP album, it was not a simple transfer of a recording but an entirely different take was used. I have noted this in a few cases such as with Robert Farnon's own original recording of "A Star is Born" which originally appeared as a single and then in the 10" LP album "A Robert Farnon Concert." Looking back, I have also noted that the Arthur Fiedler/Boston Pops recording of Leroy Anderson's "Jazz Pizzicato" on the original single and the one appearing afterward in the album "Classical Juke Box," both from the late 1940's, were noticeably not the same recording.

And we can often assume when a group of compositions by a given artist appear together in an album, especially when that artist is an established conductor, we might well assume that all of these selections were recorded by the artist himself in his own music, but such is not always the case. I raised the question above about "Portrait of a Flirt" in two performances by the Queen's Hall Light Orchestra which are notably different, one by Robert Farnon himself and the other apparently by Sidney Torch. This remains an open question but it is generally known that the original version of "Journey Into Melody" with its expanded introduction was conducted not by Robert Farnon but by Charles Williams.

Charles Williams himself was a notable conductor and composer who made many recordings conducting both the Queen's Hall group and his own orchestra, yet his "A Quiet Stroll" which exists in two renditions were both conducted by Sidney Torch.

All these situations that I refer to are enough to drive the would be cataloguer of these light music recordings absolutely insane, and I'm beginning to doubt that even David, had he been approached on these questions, would have been able to answer all of them. What I'm witnessing here is something absolutely unknown in the USA, at least to the extent I have just described. Conductor/composer/arrangers stuck with their own material, and there was never a dispute as to whom each of the selections belonged to when there was any sort of duplication - even the multiplicity of version many were wont to come out with always remained clearly distinguishable from one another, so that the only issue in question was why these individuals saw fit to release these multiple versions, although they still did not record each other's selections for one another to the same extent (or when such occurred, the distinctions were always very clear) as we are seeing today from the days of the Chappell and other mood libraries whose material is thankfully being brought to light once again. But my reasons for going into all of these situations is simply to correct any erroneous assumptions I had made in my article of just over two years ago. I also have to correct the final sentence in my article on Peter Yorke's "In the Country" for reasons I have already outlined above.

* * *

I had made a comment on Camarata's "Rumbalero" stating that though I claim to have heard a performance by Paul Whiteman leading a group at a live concert (via a radio broadcast) in 1953, I knew of no recorded performance other than the composer's own, which remains as my standard.

More recently, I discovered a posting on YouTube of a recording by a group billed as the "Broadway Orchestra," no conductor's name given, on an off-label given as "Halo." There are apparently other recordings in this series that were posted.

In my article on this piece I wrote some time afterward, I commented on this recording but did not provide any information, as the quality evidenced regarding both performance and sound was not sufficiently viable in my opinion to furnish further details, although for completeness of information, I am providing that here, even though I would still not recommend the recording and urge interested readers to stick with the composer's own recording on London/Decca records, where he is conducting the Kingsway Symphony Orchestra, despite the slight disadvantage of a bad side break occasioned in this double length selection.

The recording of De Freitas' "Fiddlesticks" that I could not recall was by Roger Roger.

With Cyril Stapleton, I had meant to also include "Latin Lady" as a selection that he recorded appearing in another version.

I hope these updates that I am offering are helpful to my readers, and as I continue to obtain additional information, I will accordingly present further updates.

William Zucker

De Montfort Hall, Leicester – Friday 24th March 2017

Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Nicholas Dodd

Presenter: Henry Kelly

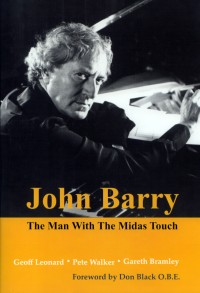

It had been the best part of a year since I had booked my tickets for this event – one of two concerts in the ‘Philharmonia at the Movies’ series with the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Nicholas Dodd. The second was to be held two days later at The Anvil in Basingstoke. I had not seen a concert of John Barry music since the Nottingham event in February 2014 so was thoroughly looking forward to it. On that occasion Dodd had conducted the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and, upon examination, the set list here was exactly the same, though two tracks in the first half had been reversed. This said, each performance always has something new to offer with a different orchestra involved and Dodd’s conducting was as immaculate as the orchestra’s playing. Compère for the evening was TV and radio presenter, and good friend of Barry, Henry Kelly – who had interviewed him at length for an issue of Classic FM in October 2001.

‘Goldfinger’ (1964) opened the proceedings and I was thrilled from my front row seat on the balcony to be able to see the whole of the orchestra, concentrating on certain sections where relevant. The rousing main title from ‘Zulu’- also from 1964 - followed and I recall this being played at a slighter faster pace than the soundtrack version. The timpanist Adrian Bending looked so confident and professional. The third title was another Bond theme – a charming instrumental version of ‘We Have all the Time in the World’ from ‘O.H.M.S.S.’ (1969), always a favourite of mine in its instrumental form.

Kelly reminded us that both of Barry’s parents had died a year or two before the 1980 film ‘Somewhere in Time’ and that these events had influenced his writing of the score. Also, that its co-star Jane Seymour – another good friend of Barry’s – had recommended him for the score. It’s certainly a very moving piece of music, especially when heard in its concert form.

Kelly also explained that the following selection was not from a film, though it was originally written for one. Not withstanding that, ‘Moviola’ (1991) was well received by the audience. After all, it is such a majestic theme, from beginning to end, and made a fine title for the album on which it appeared in 1995.

I couldn’t wait for the next selection – one that’s been a favourite of mine since I heard it played live at his comeback concert in 1998. ‘The Persuaders!’ (1971) is still one of my all-time favourite TV themes and programmes. I looked for the musician playing the keyboards but couldn’t see him - but realised later that he was slightly hidden behind his piano. Another great performance by the orchestra and solo pianist Ben Dawson. Many of the audience appreciated and remembered this theme.

‘Mary Queen of Scots’ (1971) was next, followed by the charming ‘Midnight Cowboy’ (1969) theme with a nice harmonica solo by Philip Achille. Side one ended with the usual cues from the Oscar-winning ‘Dances With Wolves’ (1991) – Kelly described this as being in ‘four movements.’ ‘The John Dunbar Theme’ gave us another opportunity to hear the fine playing of the harmonica player.

Some 20-25 minutes later the orchestra leader appeared, followed by the conductor; and programme two began with another Oscar-winning theme – ‘Born Free’ (1966). This has always been a firm favourite at John Barry concerts and one of the most-recorded themes ever. Presenter Kelly failed to refer to the next title by its correct name ‘All Time High’ but Barry’s main theme from ‘Octopussy’ (1983) has also been a regular feature in recent John Barry concerts, despite it not being that well-known. I’ve always liked the arrangement that hasn’t changed since I first heard it played in concert. Though it hadn’t got the energy of the vocal by Rita Coolidge, it still sounds great in concert form.

It was Oscar time again with the main theme from ‘Out of Africa’ (1986); followed by another personal favourite of mine ‘Body Heat’, which I recall seeing three times when it first appeared in 1981. This tune always brings forth a gorgeous alto sax solo and Nick Moss did a fantastic job with a slight variation on previous versions I’d heard.

I don’t dislike ‘Chaplin’ (1992) – it’s a great piece of music - but I’d much prefer to hear another incidental cue from this film, which is laden with some great music. Kelly reminded the audience that this film score had been nominated for an Oscar – looking back it is sad to think that both this and Jerry Goldsmith’s score to the hugely-popular ‘Basic Instinct’ lost out to Alan Menken’s ‘Aladdin’.

Another ‘blast from the past’ – with the emphasis on ‘blast’ - was up next. This was another of my favourite pieces of music that couldn’t have been more fitting to the sequence it accompanied in ‘You Only Live Twice’ (1967). ‘Space March’ was immaculate, but the ending seems to have been toned down somewhat since Barry blasted us in 1998! You can’t have a Barry concert without this title.

Barry had conducted ‘The Knack’ (1965) at his concerts in the early 70s. It’s a great theme but it never really gets going and it’s over all too quickly – a bit like ‘Wednesday’s Child’, which, sadly, wasn’t on the agenda. To me, it lacks the great organ solo played on the soundtrack and film by the late Alan Haven. Nevertheless it’s a nice laid-back theme, giving the audience time to catch their breath after the rousing ‘Space March’.

Sadly, the concert was nearing a conclusion but, as always, the ‘James Bond Medley’ ended the proceedings. As Kelly explained, all the themes were from Connery’s Bond films except one and that explanation suited me fine. Dodd furiously conducted the orchestra, which was going full tilt right to the very end. Tremendous stuff.

It had been another immaculate performance from Nicholas Dodd and the Philharmonia Orchestra - no mention of ‘the other fella’ who played Bond or some guy who composed a certain Bond theme; and rapturous applause from the audience who had thoroughly enjoyed the evening. Only one thing remained – an encore – as always ‘The James Bond Theme’.

Thank you Nicholas Dodd for a great concert and for signing my flyer after the concert. Here’s to the next one – hopefully in Nottingham.

Programme

Goldfinger

Zulu – Main Title

We Have All the Time in the World

Somewhere in Time

Moviola

The Persuaders!

Mary, Queen of Scots

Midnight Cowboy

Dances with Wolves – Suite:

John Dunbar Theme / Journey to Fort Sedgewick / Two Socks-The Wolf Theme /

Farewell & Finale

Born Free

Octopussy (All Time High)

Out of Africa

Body Heat

Chaplin

Space March (From ‘You Only Live Twice’)

The Knack

James Bond Suite:

James Bond Theme / From Russia With Love / Thunderball / 007 /

You Only Live Twice / O.H.M.S.S. / Diamonds Are Forever

Encore: James Bond Theme

© Gareth Bramley – March 2017

CASCADES TO THE SEA

(Robert Farnon)

Analysed by Robert Walton

I first found the title Cascades to the Sea quite by chance while searching for information about Robert Farnon in K B Sandved’s superb 1954 encyclopedia “The World of Music”. It was then described as a tone poem. Also mentioned were Farnon’s first two symphonies, some études and several comedy symphonettes that at the time were all a complete mystery. However the aforementioned Cascades to the Sea (1944) from which came In a Calm, bears little resemblance to a later composition of the same name. In fact the two Cascades were composed more than half a century apart. The second completed in 1997 emerged as a piano concerto or to be exact, a tone poem concerto for piano and orchestra.

Before we take an in-depth look at Cascades to the Sea, allow me to provide you with Farnon’s description and inspiration for the work:

“The music begins at the spring above a mountain stream which makes its way downhill, gradually gathering in quantity and speed to the edge of a waterfall. From there it plunges down, giving the river its own rhythm and currents as it follows a route created millions of years ago. Carving its way through mountains, meadows, rapids and deltas, it finally arrives at the open sea joining forces with an outgoing tide, flowing to the tranquility of a distant horizon”.

So let’s make a closer examination of Cascades to the Sea. The opening spellbinding (“waiting for something to happen”) chord has Farnon’s DNA written all over it. Pianist Peter Breiner tickles the ivories with the harp and together they trace a tapestry of trickles in the treble from a subterranean source. Some solid brass chords reminiscent of Stan Kenton, quote the start of Debussy’s Nuages. Throughout the work, the piano’s constant presence never lets you forget who’s in charge. An oboe keeps things moving towards what sounds like the first chord of Laura.

Then after some exciting piano, from the depths of the earth the Farnon strings rise up majestically making their presence felt in no uncertain terms with all the controlled intensity they can muster. It’s a unique sound in music. For the first time in the work, Farnon has laid down his format. After more sparkling piano, the strings and brass again powerfully push upwards, supported by the horns. The piano plays a thrilling scale passage with a touch of classically trained Carmen Cavallaro. In fact right through Cascades to the Sea you’ll hear more showy embellishments in the Cavallaro manner.

Then suddenly the orchestra sounds an alarm warning the listener of possible trouble. Don’t worry, not a problem. I suspect we’ve just reached the edge of the waterfall. All part of the grand plan. Now it’s become calm again and displaying another facet in the Farnon firmament is the seductive flute. This is followed by the oboe accompanying the piano. The strings, horn and piano play a lovely joyous melody that we’re going to hear a lot more of.

After a distinct break, (mind the gap) the piano has a short solo passage. It’s all so beautifully pianistic but not surprising as Farnon’s ability for writing for any instrument is legendary, though this is the first time I’ve encountered such an extensive work of his for the keyboard. After two more pauses, the piano plays some Bach-ish runs. Just after the catchy tune receives its most prominent exposure from the orchestra, listen for a simply gorgeous symphonic moment. The soloist echoes some of Farnon’s early decorative devices before the composer with tongue in cheek deliberately cuts short some phrases. After all this activity we eventually arrive at a typically peaceful Farnon passage with the piano, strings and woodwind. It’s back to more Farnon tremors with a further quote from the now familiar melodic fragment followed by an exciting mix of brass and strings. The solo piano plays the merest suggestion of All the Way. Some Debussyian bell-like chords soon attract the attention of the strings.

Then the penultimate Farnon surge with brass, strings and an ominous oboe while the piano continues to exercise its authority. The orchestra very gradually builds up to an absolutely thrilling ending with a difference - more an afterthought really. With single notes, the piano gently leads you to a totally unexpected experience. It’s the last thing you’d expect at the end of a piano concerto - a violin solo! The most moving moment in the entire work. In Farnon’s world that means one thing - a sublime weepy affair. It succeeds admirably and depicts a consummate convergence with the sea, where fresh meets salt. Also it’s probably one of the longest codas ever heard in a Farnon composition.

From a lowly spring to the mighty ocean, we have completed our fourteen minute journey with our guide, the piano. I hope the various signposts along the way have been helpful in identifying approximately where you are in the music at any given moment.

When I first heard Cascades to the Sea I must admit I found the piano part a bit hard to assimilate, but now after repeated playings, I have completely changed my mind. It has grown on me so much that it is unquestionably one of Robert Farnon’s finest creations and one of the most unusual piano concertos in the repertoire.

Finally, I must congratulate the Slovak pianist Peter Breiner on his brilliant interpretation of a very demanding work. And equal praise must go to the composer’s son David, who did a magnificent job conducting the Bratislava Radio Symphony Orchestra and keeping the whole thing flowing. Cascades to the Sea deserves to be heard and performed much more!

Cascades to the Sea from

“The Wide World of Robert Farnon”

Vocalion (CDLK 4146) Also on Google.

Jan Stoeckart (November 1927 – January 2017) was a Dutch composer, conductor and radio producer, who often worked under various pseudonyms, including Willy Faust, Peter Milray, Julius Steffaro and Jack Trombey. Graduating from the Amsterdam Conservatory in 1950, he began his career as a trombone and double bass player, and as a music producer for various radio shows. He composed and arranged for Dutch films and brass bands, and worked with the Metropole Orchestra and the Dutch Promenade Orchestra.

In the early 1960s, the conductor Hugo de Groot introduced Stoeckart to the de Wolfe music publishing house in London, and he obtained a contract to compose library music for that company. He wrote in excess of 1200 works; his biggest success was with Eye Level, the theme tune to the British TV series Van der Valk in the early 1970s, penned under the name of Jack Trombey.

The piece became a big hit with viewers and record buyers, and the recording – made by the Simon Park Orchestra – reached no. 1 in the UK singles charts in 1973.

As Julius Steffaro, Stoeckart composed theme and music for the famous Dutch TV series "Floris", 1969, starring Rutger Hauer and directed by Paul Verhoeven.

A cold, wet, and windy Sunday February 26th saw a second concert of British Light Music performed by the Mark Fitz-Gerald Orchestra. The venue was once again the British Home and Hospital in Streatham, South-West London. The event followed-on from the success of the first concert in 2016, and was held in aid of funds for the Home.

The programme, which was devised – as before – by Ian Finn, included a number of well-known Light Music compositions, together with some lesser-known works.

After the introductory piece, Theatreland by Jack Strachey, (which has now become the orchestra’s signature tune !), we heard Robert Farnon’s Westminster Waltz, followed by The Three Bears – A Phantasy by ‘The Uncrowned King Of Light Music’, Eric Coates.

This work has an interesting history. Originally composed in 1926, Coates made a new recording for Decca in London’s Kingsway Hall in 1949, featuring a revision of the foxtrot section [sub-titled ‘The Three Bears make the best of it and return home in the best of humour’]. The brass accompaniment is re-scored to become ’jazzier’ than the original, complete with the use of swing rhythms. It appears that Coates approached Robert Farnon, saying ‘I can’t write jazz, would you mind rewriting this for me? ‘ Bob duly obliged, although he was un-credited on the record and Coates never mentioned his assistance; apparently, it was kept a secret between the two men for many years!

Mark Fitz-Gerald was anxious to use this revised version, and although several enquiries were made, no trace was found of the sheet music. Mark therefore resorted to listening to Coates’ recording and transcribing it for performance at this concert; he told me afterwards that he believes he has achieved a pretty accurate replication of Bob Farnon’s arrangement.

We were treated to two solo piano interludes by Stephen Dickinson, featuring compositions by Billy Mayerl. In the first of these, we heard the famous Marigold – and Autumn Crocus. Later on in the programme, Stephen played Shallow Waters and Evening Primrose. A very keen gardener, Mayerl named many of his compositions after plants and flowers!

The orchestra continued with a very interesting, although little-known, work by the London-born Herman Fink – ( he of In The Shadows fame) – entitled The Last Dance Of Summer ; this was followed by the March from Trevor Duncan’s Little Suite, very familiar due to its use as the signature tune for the television series Dr. Finlay’s Casebook.

Next-up was a composition by ‘our own’ Brian Reynolds – Elizabethan Tapestry, in a arrangement made for Brian by the late Cyril Watters. We were then treated to a lesser-known but lively composition by Derby-born Percy Eastman Fletcher, from his suite of Three Light Pieces, entitled Lubbly Lulu, after which the members of the audience were encouraged to join-in with singing the lyrics of John Bratton’s world-famous Teddy Bears’ Picnic – which they did, lustily!

From the set of Nell Gwyn Dances by Edward German we heard the Pastoral Dance, following which a member of the string section, the soprano Tessa Crilly, stepped forward for a lovely rendition of I Could Have Danced All Night from the musical show My Fair Lady, by Lerner and Lowe.

The next item was by a ‘local boy’ – Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, who spent much of his tragically short life in nearby Croydon. From his well-known Petite Suite de Concert, we heard Sonnet d’Amour.

Stephen Dickinson then joined the ensemble for a performance of Percy Grainger’s ‘clog dance’ Handel In The Strand. Although scored for full orchestra, the piece was notable for not including the double basses!

The final ‘billed’ item was another Eric Coates masterpiece – in fact probably one of his most famous and frequently-played tunes – the march Knightsbridge from his London Suite.

After a rousing response from the audience demanding an encore, Mark Fitz-Gerald and his orchestra brought the proceedings to their final conclusion with the well-known Jamaican Rhumba by the Australian composer Arthur Benjamin.

It was great to be present at this most enjoyable afternoon, presented by an such an enthusiastic musical director – and champion of Light Music – and his excellent orchestra, and it is hoped that they will return once again in 2018.

Very many thanks to Mark Fitz-Gerald, to Ian Finn, and to the British Home and Hospital at Streatham.

© Tony Clayden

February 2017

(Mourant)

Analysed by Robert Walton

For many years I have been meaning to analyse Walter Mourant’s Ecstasy but somehow I never got around to it. I can’t believe I left it so long, because it’s one of the few openings that made such a lasting impression.

The first time I heard it was in 1958 when I was an announcer in Whangarei, New Zealand, at 1XN Radio Northland. Those were the days before sealed airtight cubicles when there was an open window in the studio overlooking an attractive garden and heavily wooded hills. Very civilized! Incidentally four years before, sitting in that very same announcer’s chair was Corbet Woodall later to work for BBC Television in London as a newsreader. We were both learning the ropes of broadcasting on live radio. I met him only once in 1976 at his Marble Arch delicatessan in London.

The 78rpm Brunswick disc (05153) in question featured clarinetist Reginald Kell with Camarata’s Orchestra. As I placed it on the turntable and cued it ready to go on air, it was just another recording.

After a few seconds of introduction, mysterious high strings carried me off to another world. I was hooked. Harmonically it kept wandering off into Debussyian byways as well as quite a bit of diving down, but always returning to the home chord on a major 9 like Poinciana. And speaking of Poinciana, occasionally you’ll hear the David Rose string sound. Some of the chords reminded me of Tony Lowry’s Seascape. I wasn’t a bit surprised that Tutti Camarata was in charge as every aspect of the recording indicated quality.

Then taking over this meandering tune, Kell makes his first appearance with the orchestra and is soon joined by a violin, with which he produces an atonal moment. After going totally solo for a few bars, the clarinet is once more partnered by the orchestra. Note Kell’s distinctive vibrato for which he was famous. From here right until the end it’s the mournful clarinet of ‘roving’ Reginald playing the melody supported by those now familiar harmonies.

At this juncture it might help to give you a brief bio of the comparatively unknown American Walter Mourant (1911-1995) who began his career in jazz. One of his best-known works was Swing Low Sweet Clarinet performed by Woody Herman and Pete Fountain. Clearly Mourant loved writing for the clarinet. Also his chamber music and orchestral compositions are well worth Googling. Various assignments included arranging for the Raymond Scott Orchestra at CBS and composing a March of Time theme for NBC.

Ecstasy is that the somewhat dreary second half of the arrangement does not fulfill the initial promise of the ecstatic opening. In spite of that, I wouldn’t dismiss it out of hand but still recommend you to give it a listen and enjoy.

By Robert Walton

During the 1990s while living in Bath, my wife and I regularly attended the winter series of symphony concerts at the Colston Hall in Bristol. We always sat in the same seats in the choir stalls behind the orchestra facing the conductor. To all intents and purposes we were part of the percussion. In fact a certain timpanist was constantly tuning up. We were so close we could follow the music on his stand. We saw many of the world’s famous orchestras and conductors. Some Russian and East European orchestras were clearly struggling financially because their music was obviously well worn, not to mention their threadbare dinner jackets, but it didn’t affect their performances in the slightest.

And talking of Russian music, a member of the audience who sat right up at the back behind us looked the image of Tchaikovsky! And he never missed a concert but I’m sure he had no idea he looked like the great composer.

Which brings me to the noted popular 20th century composer-arranger-conductor from Webster Groves, Missouri, Gordon Jenkins who certainly didn’t look like him. His music though clearly caught the essence of Tchaikovsky. Jenkins’ detractors often unkindly placed his name at the top of the schmaltz lists. He might have been a 20th century clone of Tchaikovsky but cleverly incorporated the Russian’s style into his own compositions and orchestrations in his own individual way. In fact he could be said to have kept romance alive and well.

Jenkins’ Green from “Tone Poems of Colour” conducted by Frank Sinatra was inspired by a poem of Norman Sickel, a one-time radio scriptwriter for Sinatra. This 1956 recording session with a symphonic- sized orchestra celebrated the opening of Capitol’s new pancake-shaped skyscraper in Los Angeles known as Capitol Records Tower.

At the opening and closing of this tone poem, some Jenkins one-finger piano was required, but the man himself wasn’t available. So Sinatra’s pianist Bill Miller brilliantly simulated Jenkins’ so-called hunt-and-peck piano style (like a hen searching for food, the finger creeps along the keyboard ready to ‘pounce’ on the next note). When sad strings enter I dare you not to be moved. This is followed by the heavenly oboe and flute. You may hardly notice the French horn playing a legato counter-melody but without its contribution it would seem incomplete.

When the strings get even more aroused, the emotion generated is conspicuously overwhelming by its presence. So moving in fact, it’s beyond words and tears! This is what music is all about. We have been elevated to a higher plain in much the same way as Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony does.In fact Green could be described as that work in miniature. The horn continues to decorate, adding its own special hue to the mix. The essential Jenkins has now come to life with this sublime songlike strain. I know Pyotr Ilyich would have approved. Listen out for a bit of Borodin (Stranger in Paradise)in slow motion borrowed from ”Prince Igor’s” Polovtsian Dances.

And with a definite pause, the second part of the melody doesn’t disappoint, continuing its dramatic journey downhill played by unison violins at the bottom of their range. We assume the orchestra is preparing itself for a big ending. “But no!” as Danny Kaye might have insisted. After numerous comings and goings with the said woodwind, strings and horn, stand by for two more thrilling string flourishes. The horn and flute finally bring Green to a gloriously peaceful close. But not quite. Bill Miller’s single note piano has the last say but not in its normal middle register. This time it’s uncharacteristically higher than usual.

If you’ve never heard any Tchaikovsky or indeed the 6th Symphony (ThePathétique) I can’t recommend Green highly enough as the perfect Tchaikovsky taster. If you like this, you’ll adore the real thing!

Green, originally from “Tone Poems of Colour”

Capitol (CDP 7 99647 2)

Also on “Scenic Grandeur” from Guild’s Golden Age of Light Music (GLCD 5145)